Decisions about women’s health have historically been made by men.

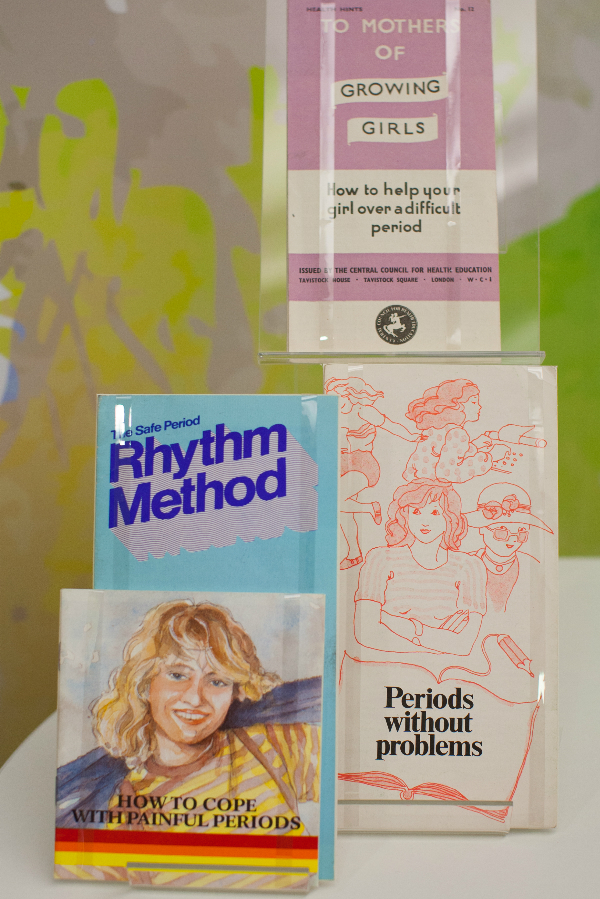

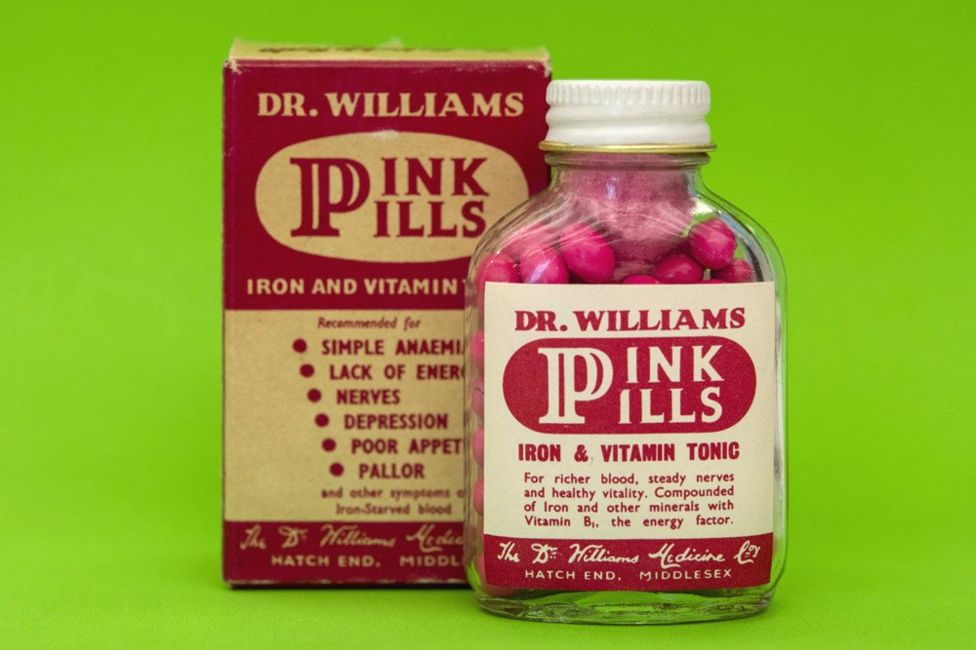

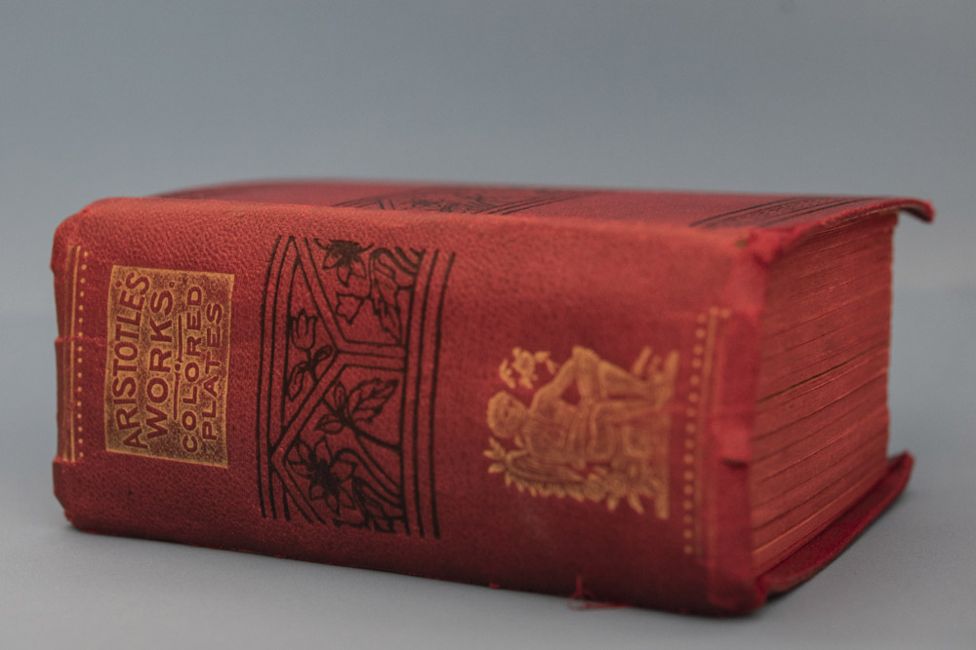

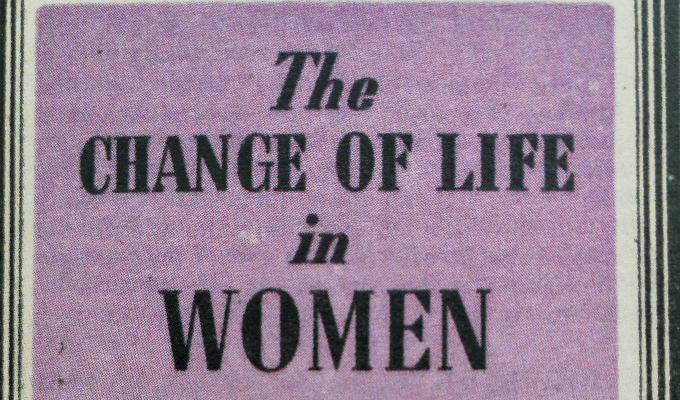

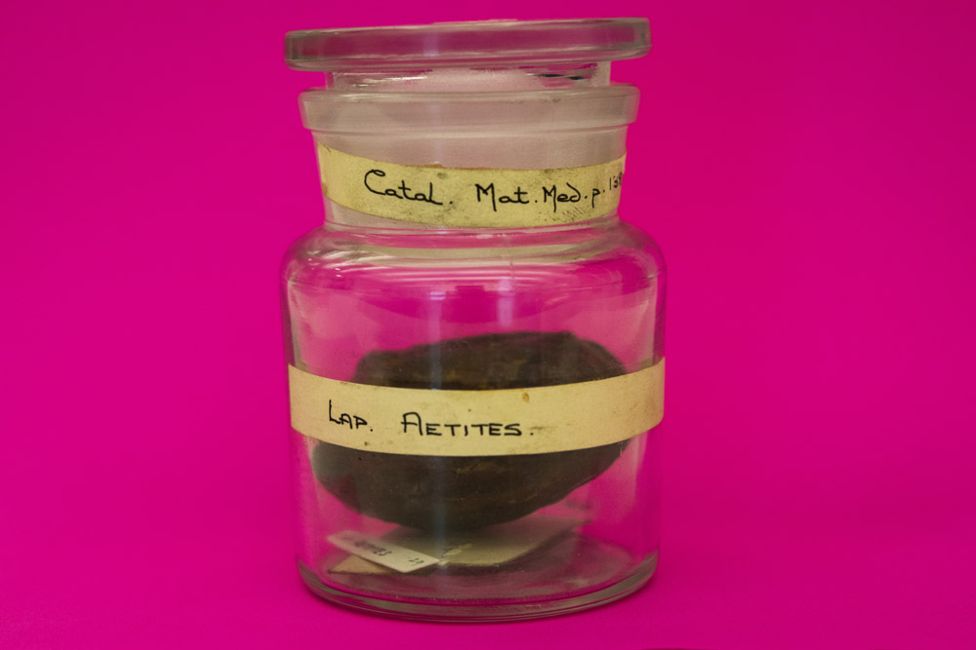

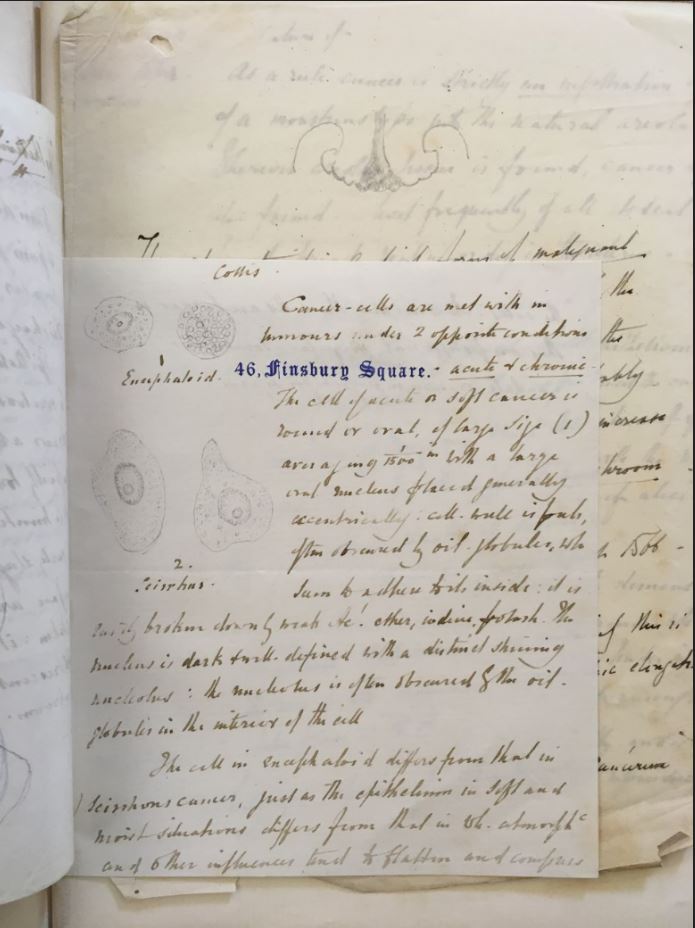

For the Victorians, the menstrual cycle was considered a disease. Women found all sorts of ways to find out more about their periods and learnt from female relatives. Some would even source secret texts on women’s health, often disguised in the dust jacket of more ‘acceptable’ reading material.

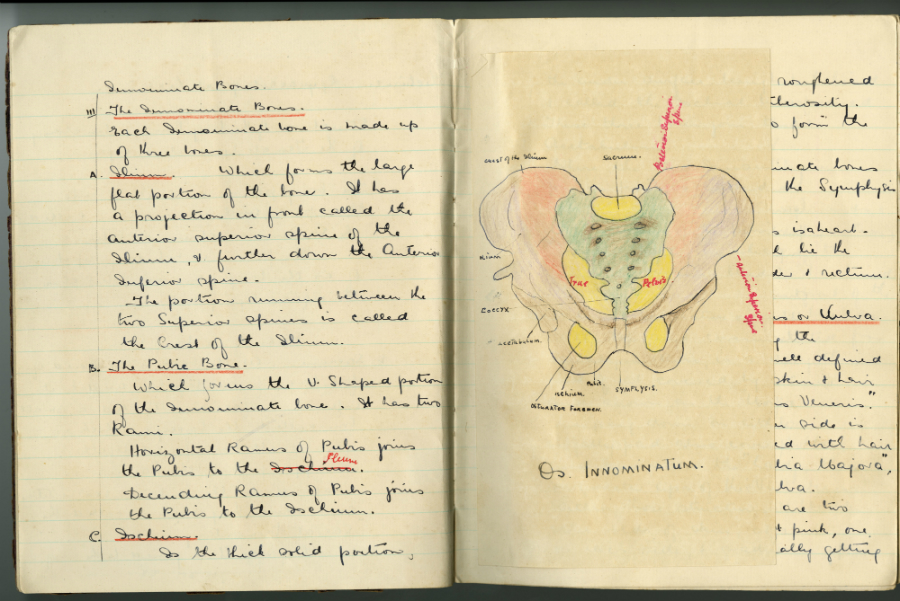

How did nursing change this? As the role of women in health care grew, so did an understanding about women’s health and biological cycles. Nurses became advocates for women, in a position to air previously hidden topics.

The introduction of the contraceptive pill in 1961 changed when and how much women bleed. It helped move away from medically assumed norms to cycle lengths and flows unique to the individual. More and more women were able to better predict the symptoms of their own biology.

Women today have more control over their periods than ever. Bolder attitudes have seen campaigns to abolish the ‘tampon tax’ and charities working to ensure all women get access to menstrual supplies. Nurses play an important part in this changing atmosphere. As more non-surgical options have become available for women, like mirena coils and hysteroscopy, nurses have been at the forefront of embracing and delivering these treatments.