Josephine Angois

“Have had a very busy night and no time to sit down… but feel less tired than when there is nothing to do.”

Introduction

Descended from Calais lace workers and born in Nottingham, Josephine Louise Angois was a volunteer nurse in the 20th century’s bloodiest war. She lived an extraordinary ‘ordinary’ life. Through the pages of her scrapbook we can explore her years in wartime.

Angois’ father, Paul Angois, was born in France in Pierre les Calais, a village associated with the lace industry. As a teenager Paul moved with his family to Sneinton, a village near Nottingham, also associated with lace-making. Rather than pursuing a career in lace, Paul became an engineer. In 1881 he married a French girl, Marthe Guinois, from Orleans. Marthe had been living in Darlington as a French teacher. On 30 May 1884, three years after Paul and Marthe had married, Josephine Louise Angois was born.

A year after Angois’ birth her father set up a small bicycle workshop in Raleigh Street, Nottingham, with a partner, Richard Woodhead, adopting the brand name Raleigh. By 1889 the firm was very successful, with a nominal capital of £20,000. Paul Angois held a secure position as director responsible for design. Sadly, after this upward change in the family fortunes, Angois’ mother died. Angois was only eleven years old. Within a year her father had remarried, an English lady this time, Sarah Ellen Holmes. By the 1901 census Paul was comfortable enough to be listed as a ‘retired cycle manufacturer’.

Angois [left] circa 1915

War on the horizon

... in these abnormal times let it be taken for granted that every woman is doing her best

Angois did not train as a nurse, but she joined the British Red Cross Voluntary Aid Detachment, Nottingham 40 in 1913. She learnt first aid and home nursing, as well as taking cookery classes. These volunteers became known as VADs and had to pass examinations to become certificated. It is likely that Angois’ training took place at Welbeck Abbey in Sherwood Forest. This was the 6th Duke of Portland and Duchess Winifred’s home. As soon as war broke out they had established an auxiliary Red Cross hospital here. You can see the Duchess conducting a Red Cross Inspection on 31 July 1914 in the scrapbook. On the same page we find a picture of a number of Voluntary Aid Detachments, gathered in the Abbey’s huge Indoor Riding House.

Background image: Voluntary Aid Detachments. Identified by Gareth Hughes, Portland Collections Manager

VAD training

Less than a year later, in April 1915, Angois went to number 83, Pall Mall, where she was issued with an Identity Certificate, number 3786, by the British Red Cross. The number is etched on the reverse of her Red Cross badge. She attached this to her scrapbook with a red, white and blue ribbon. One of Angois’ Red Cross cards records the fact she was a J.W.V.A.D. – a Joint War VAD. Most VADs were under the control of the War Office, but others were in the service of the Joint War Committee. This combined the efforts of the British Red Cross and the Order of St. John. These volunteers staffed rapidly expanding hospitals and hostels. Many of them, like Angois, served overseas. They were given some living allowances (Angois received three francs a week for laundry) but no salary for their work. Belonging to the Joint War Committee must have meant something to Angois, as she put part of her brassard (armband) on the cover of her scrapbook. It shows the Order of St. Johns in the top half, and the Red Cross on the bottom. This was kept alongside her Red Cross badge.

During 1915 more nurses were needed to staff the increasing number of hospitals and casualties and the VADs, originally trained for service at home, were now recruited for special service overseas. Angois was one of them. She received a telegram at home – she was called to serve in No. 1 British Red Cross Duchess of Westminster’s Hospital, in Le Touquet-Paris-Plage, France.

Report here tomorrow morning prepared to start for France

No. 1 British Red Cross Hospital

Angois’ scrapbook is filled with postcards of the No. 1 British Red Cross Duchess of Westminster’s Hospital, and images of the town, Le Touquet. The hospital was opened by Constance, the Duchess of Westmister at a former casino with her own money and donated funds. Le Touquet was a fashionable seaside town, and with surrounding woods and golf courses, it had been a popular holiday destination before the war. The No. 1 British Red Cross Hospital was a Base Hospital, and took casualties from the front lines Casualty Clearing Stations. Le Touquet was very close to Etaples, which was a massive British base with over twenty hospitals.

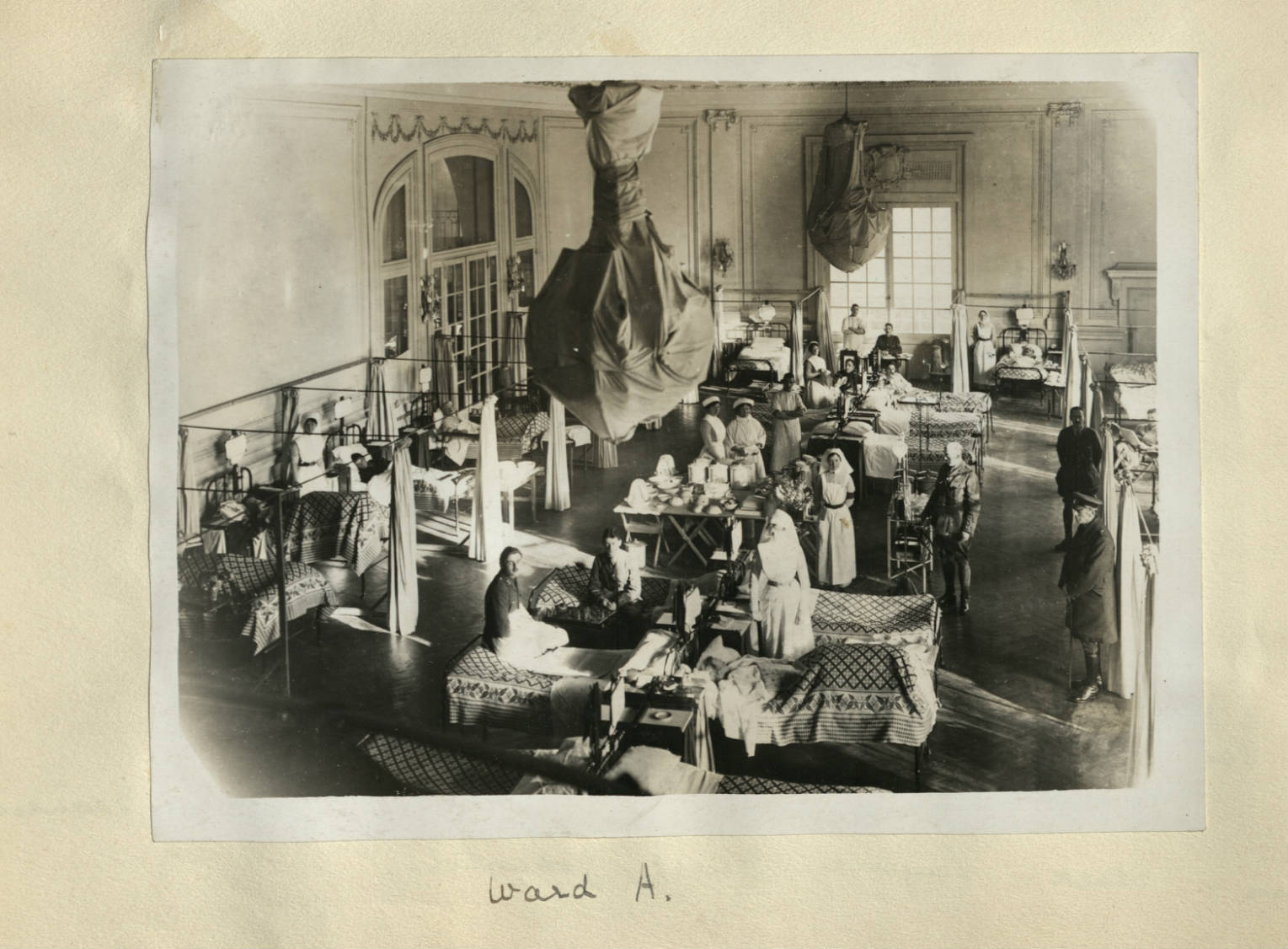

The No. 1 British Red Cross Hospital was quite a small hospital, with only four wards and 150 beds. Angois kept images of the interior of the hospital. Her pictures show Wards A and B to have been spacious and bright, clean and tidy. The chandeliers were wrapped up in protective cloths with screens on frames around each bed. Although set up initially for all ranks, the hospital soon took in mainly officers, who received a greater degree of privacy.

The Staff of Ward A

Captain Fraser

Josephine Angois

Miss Carson

Miss Price-Jones

Miss Ram

Miss Villiers

Mr Dick

Sister Hallett

Sister Morris

Sister Rearden

Sister Shankland

Sister Taylor

Sister Vincent

The Staff of Ward B

Major Brandson

Major Pritchard

Miss Densham Matron

Miss Durst

Miss Johnstone

Miss Layard

Miss Stack

Sister Butterworth

Sister Gash

Sister Giles

Sister Harris

Sister Mitchell

Sister Oakden

Angois documented the staff from Ward A and B, you can see the mix of nurses and VADs (identifiable through their Red Cross) required on the wards. Thankfully, Angois was very thorough and each person is named. We can see her sitting on the bottom row, second to the right in Ward A.

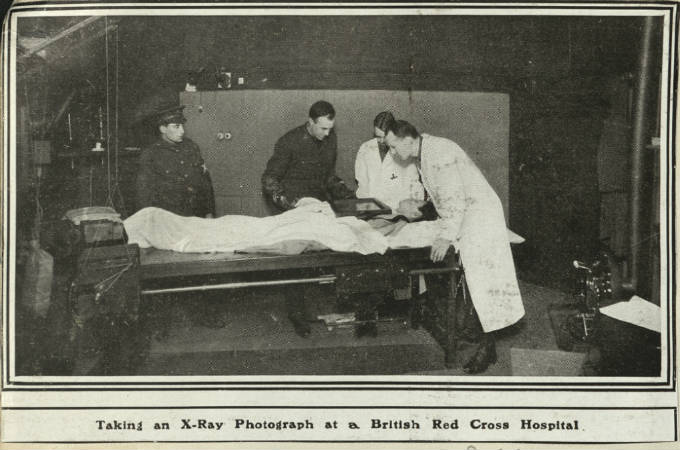

As well as four wards the hospital had a laboratory and an X-ray department. Captain Stone was the radiographer. Nine medical officers are named in a picture of the medical staff, including Colonel Watson, the Commanding Officer.

Constance, the Duchess of Westminster, the patron of the hospital, also took an active role as a nurse. In a newspaper cutting Angois saved she was described as ‘an excellent masseuse’ along with two nurses, Miss Richmond and Miss Molesworth. Angois must have admired them, or was proud to serve with them, as she cut their picture from a magazine.

Medical Officers from the No. 1 British Red Cross Hospital

Captain Adjutant Eilank

Captain Bacer

Captain Fraser

Captain Stone

Colonel Watson

Major Branson

Major Pritchard

Mr Allday

Mr Dick

Life as a VAD nurse

Angois' Service Agreement gives an insight as to what was required of her. She agreed to devote her:

whole time and professional skill to my service […] I shall be subjected to military discipline and will obey all orders given to me by any superior officer of the Hospital.

It would appear that the VAD nurse was to mainly do as she was told. Angois seems to have adapted to this rigorous lifestyle very well. She wrote in a postcard to her parents:

...have had a very busy night and no time to sit down, had two trains in so are very busy, four operations in the night, but feel less tired than when there is nothing to do.

When not on duty the scrapbook shows Angois and her colleagues were able to go walking in the area, which had sand dunes, a beach and a forest. The picture postcards she pasted in the book show a number of large houses in the area. Angois has noted these were 'billets during summer 1915'. Most likely Angois and her colleagues lived together in this house, or one very similar to it.

Have just had a scramble up the Dunes, it is simply lovely, this place beats Bournemouth any day. We ought to have a holiday here when the war is over.

Angois also made attachments beyond her fellow VADs. On the back of Angois’ book there is a small piece of blue fabric with a gold wire emblem. The fabric is the horizon-blue cloth for French soldiers' uniforms that was issued in 1915. The gold wire implies that the badge was worn by a senior officer, most likely a 'carbonnier observateur’. The role was dangerous, the soldier having to go close to the line to check how well the artillery were reaching their targets – and not falling short or injuring their own troops. So, whose uniform did this belong to, and why did Angois save it?

The badge of a 'carbonnier observateur’ pasted to the back of Angois' Scrapbook. Identified by Ian Sumner.

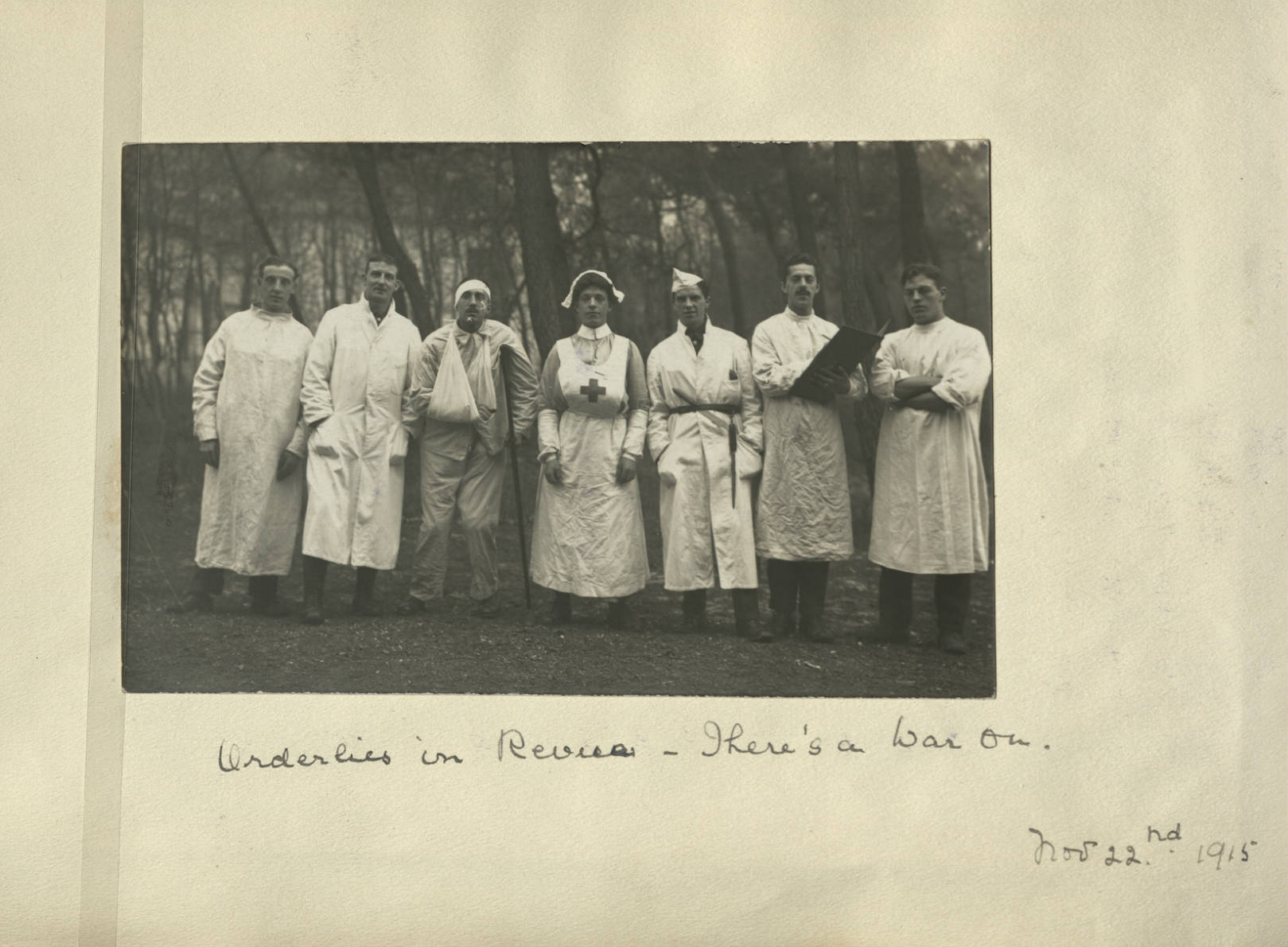

Entertainment

The hospital seems to have placed a high emphasis on lifting the spirits of the men they cared for, as well as for the staff themselves. This may be seen in the number of diversions they held. Angois pasted a photograph of the Orderlies revue 'There's a War On' in the scrapbook, you can even see one of them dressed up as a VAD.

4 pm

Final of Inter-troop wrestling.

On horseback.

In May 1916 the army put on a Programme of Sports which involved some of the cavalry. This included a; jumping competition, inter-troop wrestling (on horseback) and a tug of war (dismounted). Another concert, held on the 13 June 1916, featured the Convalescent Camp Band. The finale was a rendition of a patriotic song – 'Our Flag'. Angois appeared in at least one of these entertainments. Her name is on a typewritten concert programme for 'Patriotic Scena' in which she is 'France'.

Nottingham

It's All Right the Sherwoods Are There

Throughout her scrapbook Angois kept a record of news to do with her hometown throughout the war – especially keeping an eye on the exploits of the Sherwood Foresters – a Nottinghamshire regiment. It's unclear whether she knew someone in the Foresters, or was recording her hometown pride. Perhaps it was a mix of both.

Background image: The Sherwood Foresters who 'quelled' a Sinn Fein rebellion

5th Southern General Hospital

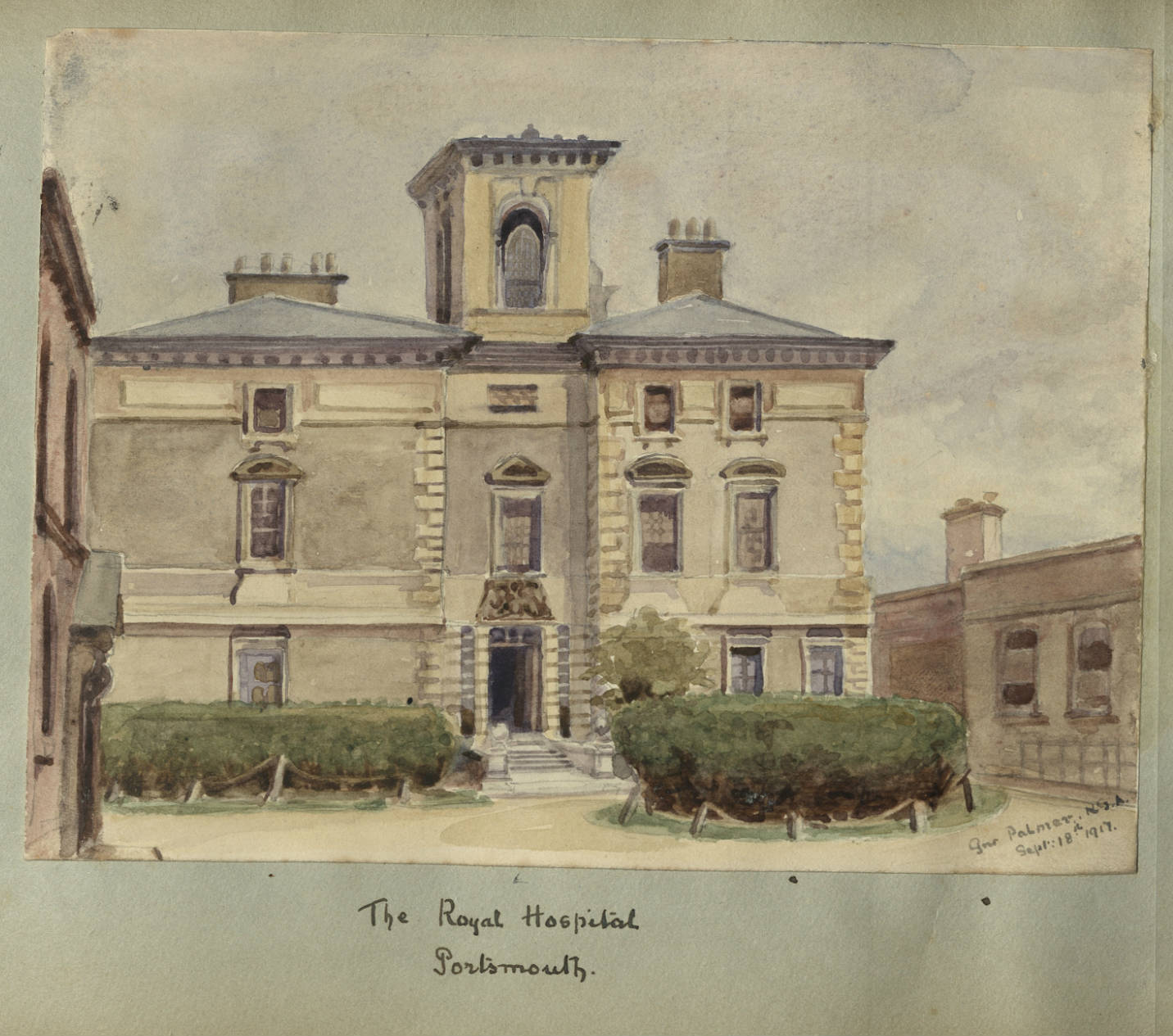

Angois started work at the 5th Southern General Hospital, Portsmouth, in February 1917. The hospital was an enormous combination of sites across the Portsmouth and Gosport area, with a total of beds exceeding 1,000 by 1916. Angois worked in a few locations across the complex. She was first sent to the Royal, which was mainly for Officers' convalescence.

Towards the end of the war she was nursing in Fawcett Road, a requisitioned Girls' Secondary School. The central hall of the school had been converted into a ward with four rows of beds. A wide gallery ran around the hall, some twenty feet above it, where patients and visitors could walk about or have a smoke. The Matron's quarters were nearby, so she had close control over the whole hall and over access to the gallery. Many small wards led off it, mostly used as officer's rooms and operating theatres.

German patients were also being nursed in Fawcett Road although in a separate ward and under guard. It is not clear whether Angois nursed them. Their presence excited local curiosity, but the unnamed nurse assigned to their closely guarded quarters reported 'they gave no trouble, are very grateful and glad to be where they are'.

Whilst at the 5th General Angois seems to have enjoyed good relationships with her many colleagues. In her scrapbook she collected crammed pages of autographs from staff of all ranks from two of the different areas she nursed in – Headquarters and the Royal Hospital.

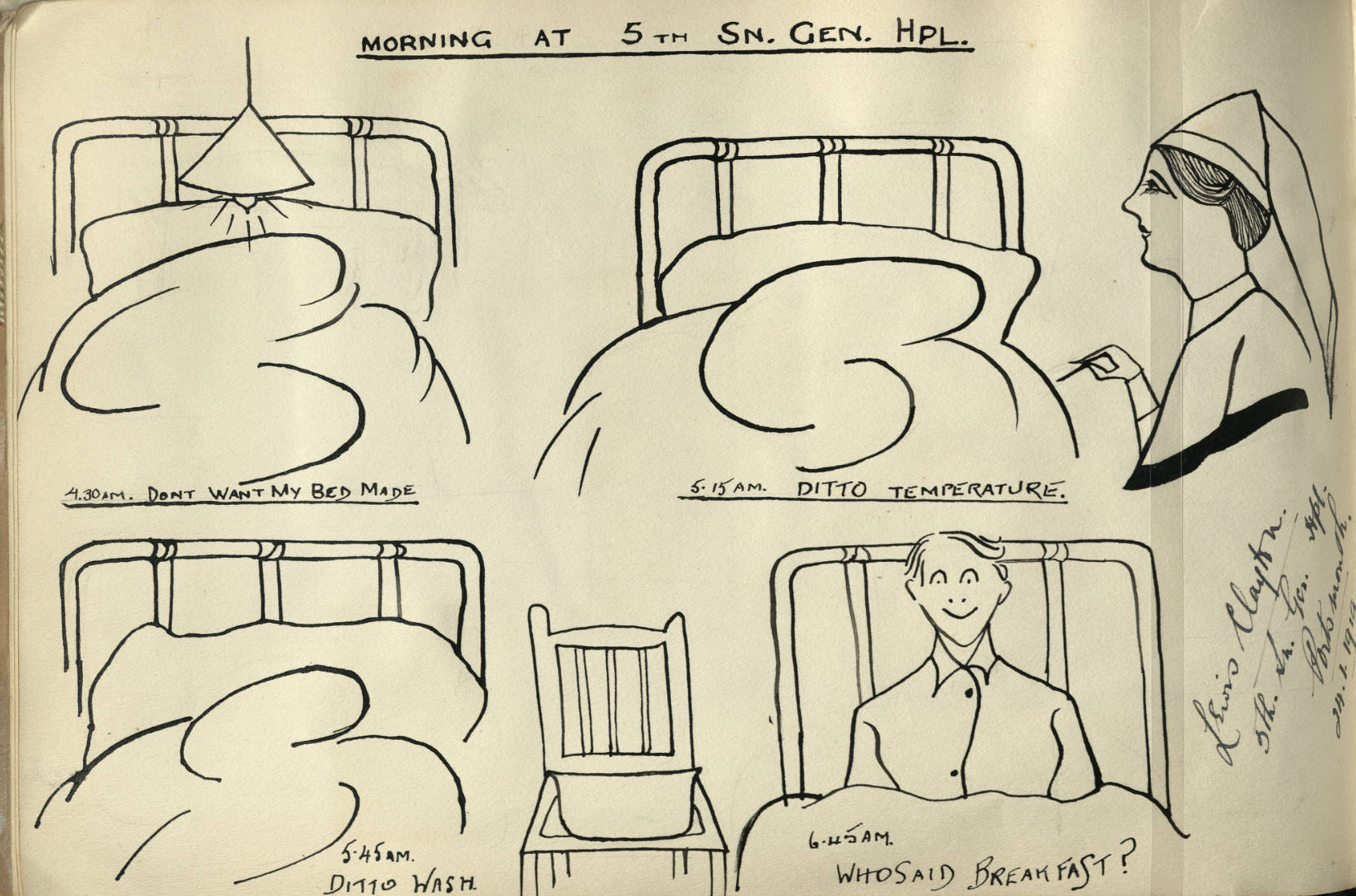

Who said breakfast?

A cartoon by patient Lewis Clayton shows the morning routine in the hospital, with a nurse attempting to make the bed take the temperature and wash a grumpy patient. The only thing to rouse him is his breakfast. Undoubtedly this would be a scene Angois would be familiar with, she probably had this discussion with patients many times over. For Clayton to ridicule himself, or the actions of others in the ward, shows a genial bond between him and Angois. He was not the only patient to do so. Whilst in York Ward ‘J.T.’ pokes a little gentle fun at the nurses and orderlies, caricaturing their actions on the ward (above image). Another good-humoured image shows a patient suffering from the attentions of a nurse with a shaving razor.

5th Southern General Hospital is not as fully documented as her first term of service in France. Nonetheless Angois was proud of her colleagues at the 5th Southern – she pasted newspaper cuttings in her scrapbook about honours awarded to the staff who served there. Angois nursed here until the end of the war. Armistice did not cause the immediate end of military hospitals or the need for nurses and VADs. Angois remained at her post in Portsmouth until 2nd April 1919 when a letter came terminating her contract as a VAD with only four days’ notice. Angois’ wartime service was over.

After the war

It is hard to tell what impact her experiences during the Great War had on Angois. We have only her scrapbook, filled with pictures and drawings, to look for clues. The many pictures of nursing colleagues and friends enjoying time outdoors, and often with patients, do not speak of misery or hardship. The humour of the British 'Tommy' shines through in the cartoons she kept, as does their talent in lovely drawings. Images of patients with their nurses are endearing, and suggest the hospitals she worked in had a warm friendly atmosphere between the patients and staff.

After the war Angois remained in Nottingham for a long time, with her father Paul, at Hillcrest, Malvern Road. He died in 1938. She subsequently moved to Goring-by-Sea and lived with Elizabeth Hunstone – known as Lizzie. Angois and Hunstone purchased a grave together in 1958 at Durrington Cemetery. Hunstone died first, on 16 May 1963 and Angois two years later, on 25 November 1965. Her cause of death coldly reads: Senility. The many photographs Angois placed in her scrapbook are a wonderful legacy, documenting in detail the experience of the VAD and their crucial contribution to the war effort.

Angois and Hunstone’s headstone. Image courtesy of Durrington Cemetery.

Sources

Keith Allmark, Researcher, Chester

Donna Bish, Researcher, Portsmouth

Gareth Hughes, Collections Manager, Portland Collection

Tracey Lillie, Durrington Cemetery, Worthing

Louise Martin, Archivist and Records Manager, Grosvenor Estate

David Rees, Researcher, Chester

Ian Sumner, Researcher, Beverly

Charlotte Yeoman, Researcher, Priory School, Portsmouth

References

Image credit: Angois and Hunstone’s headstone. Image courtesy of Durrington Cemetery.

Davies, Brian, A Short History of Priory School, Self-published, 1997.

Gange, Molly, Hospitals of Portsmouth Past and Present, Ensign Publications, 1988.

Gates, William, Portsmouth and the Great War, Evening News and Hampshire Telegraph, 1919.

Light, S. VAD Life. (2017). http://www.scarletfinders.co.uk/183.html [Accessed 30 Nov. 2017].

Sadden, John, Keep the Home Fires Burning: The story of Portsmouth and Gosport in World War 1. Portsmouth Publishing and Printing Ltd, 1990.

Territorial Hospitals, The British Journal of Nursing, 53, December 5, 1914, Page 445.

Census Returns of England and Wales. Census 1871, 1881, 1891, 1901, 1911, Kew, Surrey, England: The National Archives of the UK (TNA). Accessed: Ancestry https://www.ancestry.co.uk/

The National Archives of the UK; Kew, Surrey, England; WWI Service Medal and Award Rolls; Class: WO 329; Piece Number: 2317. Accessed: Ancestry https://www.ancestry.co.uk/

The Chester Courant, 12 August, 1914. Page 4. Column 7.

Territorial Hospitals, The British Journal of Nursing, 53, December 5, 1914, Page 445.

Hospital Records Database, The National Archives.

List of auxiliary hospitals in the UK during the First World War. Page 22. Available at www.redcross.org.uk. [Accessed 29 Nov. 2017].