Jessie Akehurst

"Then come all ye to Somerville with wounds or with disease"

TFNS

When the First World War broke out in 1914, Jessie Margaret Akehurst already had fourteen years nursing experience under her belt. Within the year she had enrolled in the Territorial Force Nursing Service (TFNS). In 1915 she received her first military posting and was sent to Somerville, Oxford. Here she received a scrapbook for Christmas, and began to collect entries from the people she met throughout the war.

To join the TFNS, Akehurst had to prove her worth. All nurses were required to have at least three years general training in a recognised hospital or infirmary, and come recommended by their matrons. Applicants also had to be between 23 and 50 years of age. Akehurst had started her training in 1900, and became a qualified midwife in 1904. At this time midwifery and district nursing were a combined profession, so her duties covered both.

Life at Somerville, Oxford

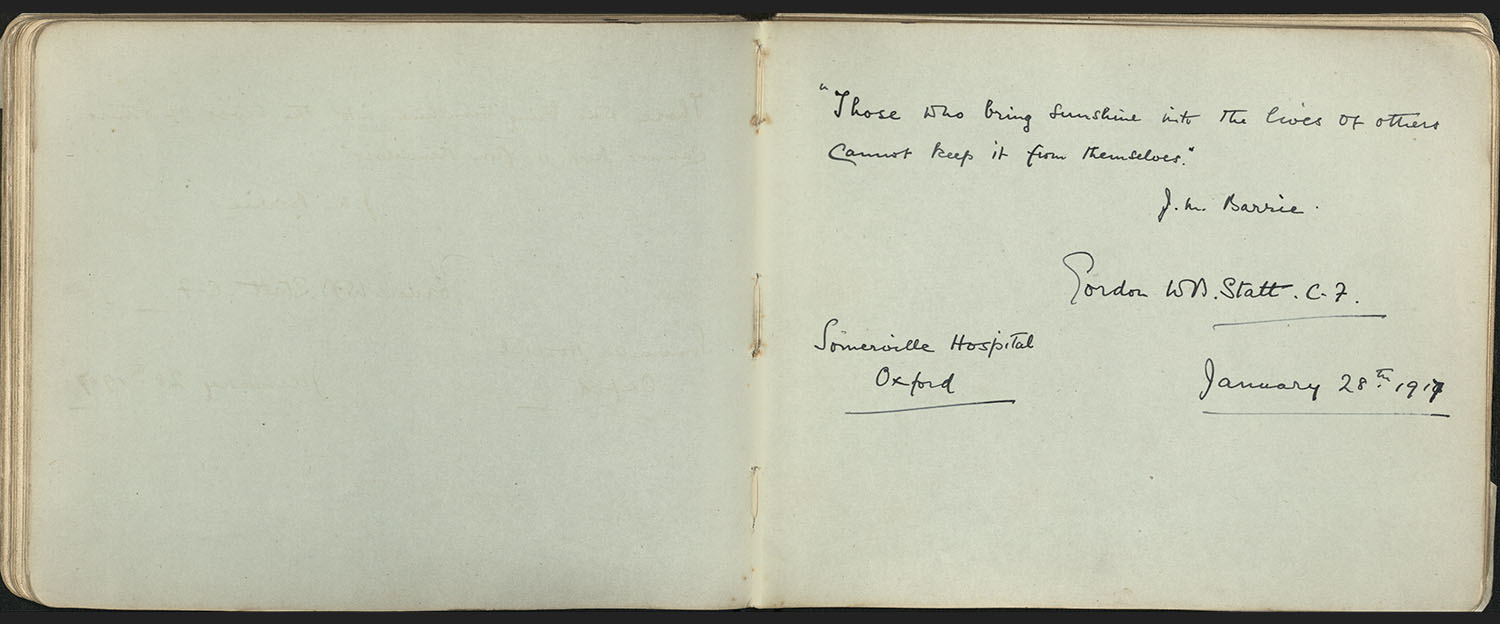

Many of those signing the scrapbook indicate they are patients from the Third Southern General Hospital in Oxford, a combination of existing hospitals and requisitioned university buildings. One of these buildings was Somerville College, where Akehurst began her work.

In April 1915 Somerville was taken over by the War Office. Vera Brittain, at this time a student at the college, records ‘the excitement of the Somerville students of their changed circumstance.’ By December 1915, the time Akehurst was at Somerville, Brittain had left to become a Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD) in Camberwell. Many of her contemporaries did the same.

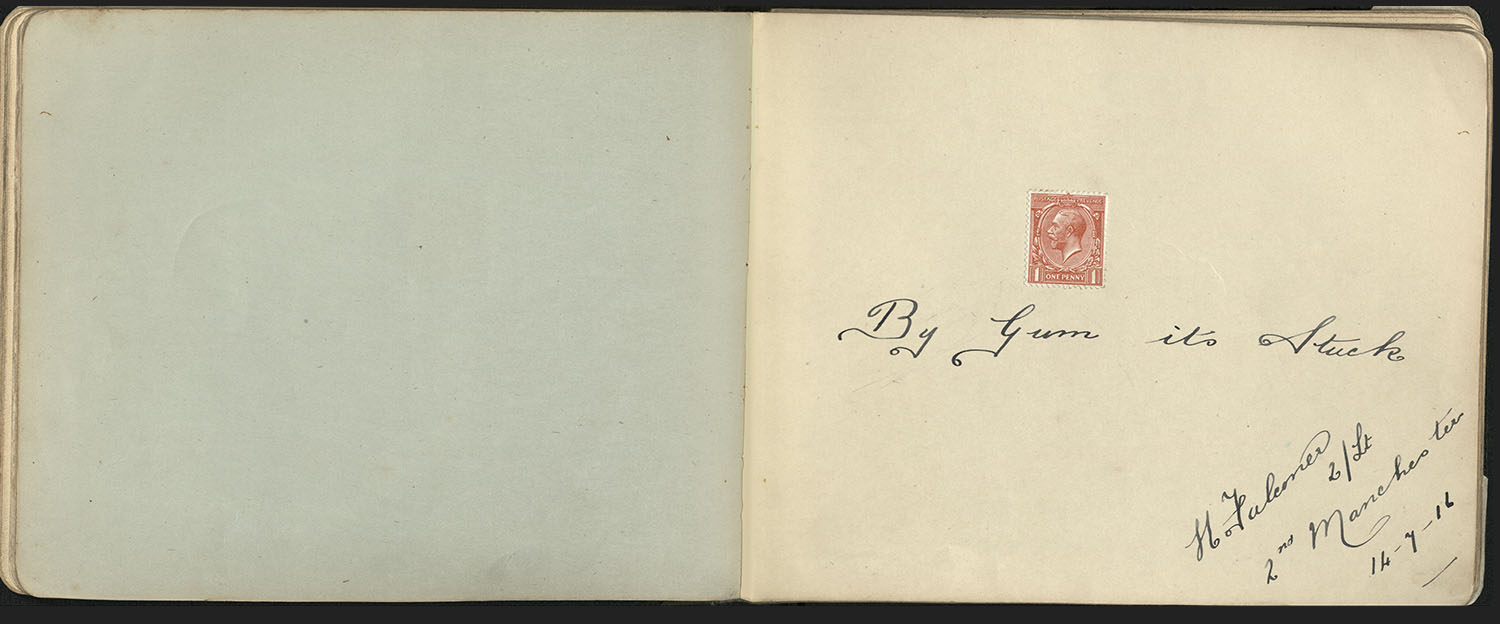

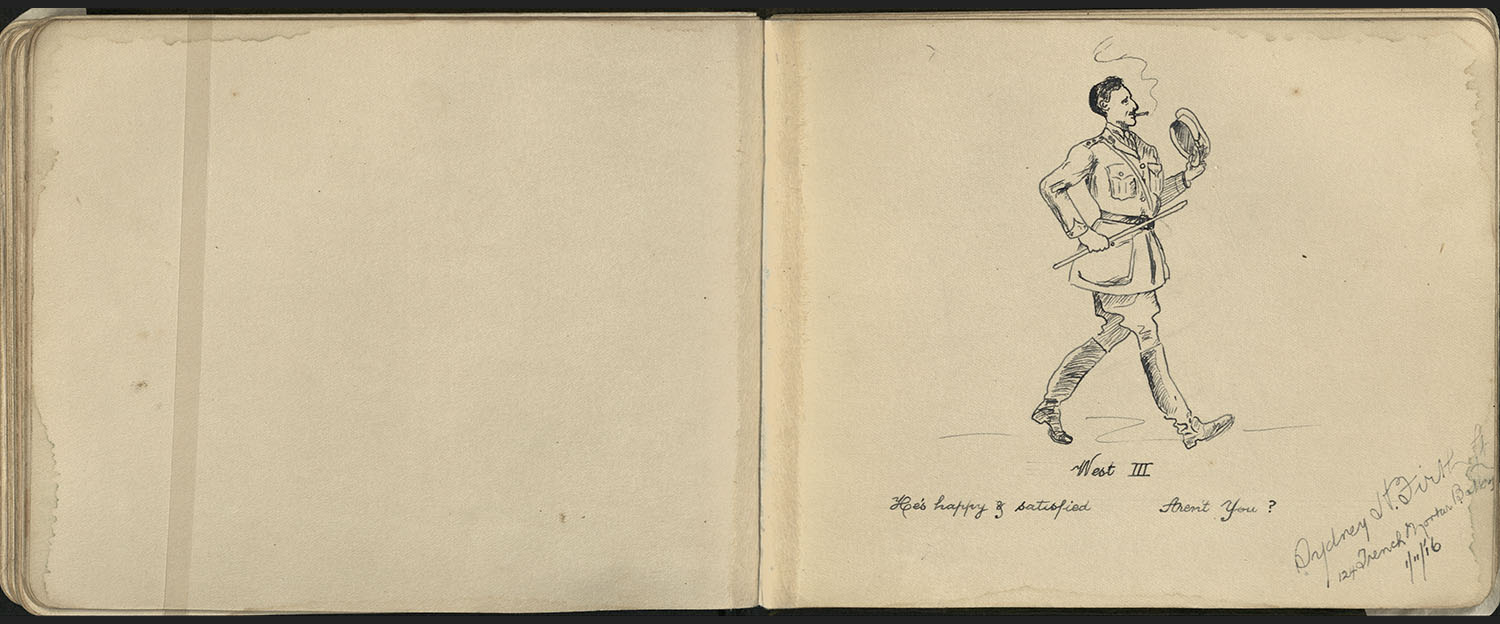

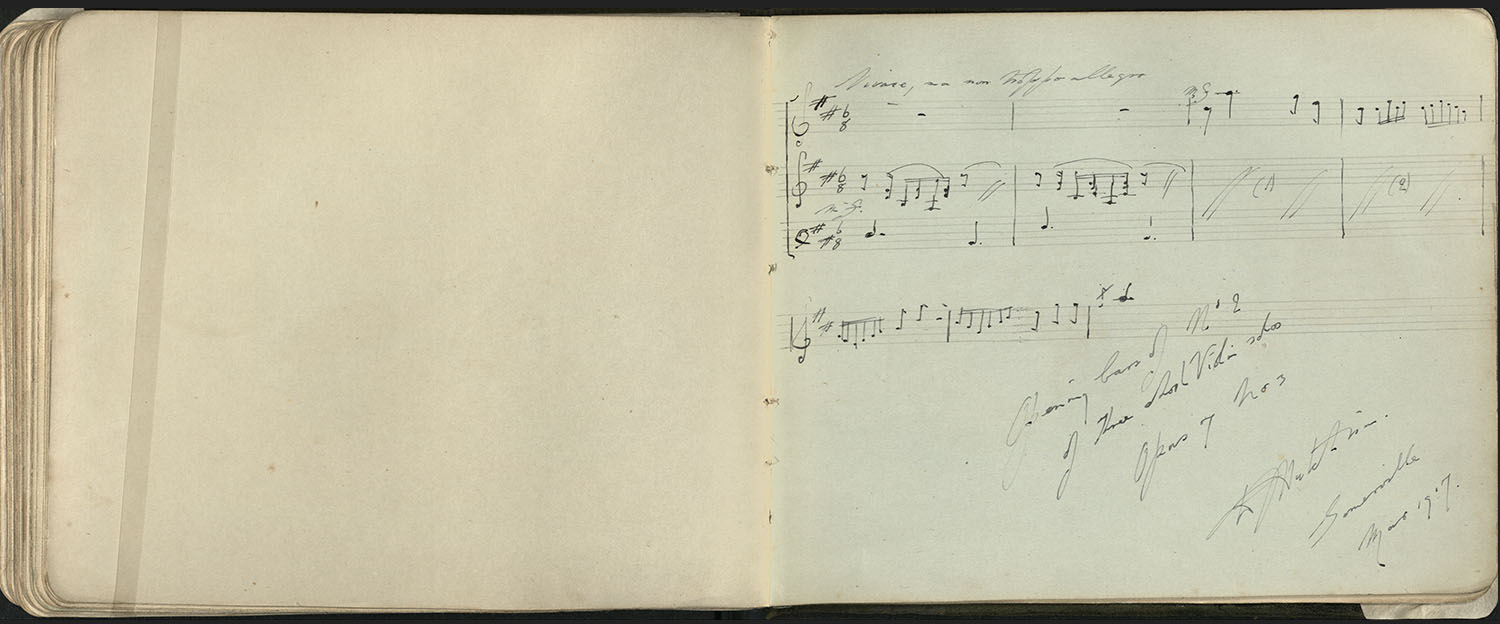

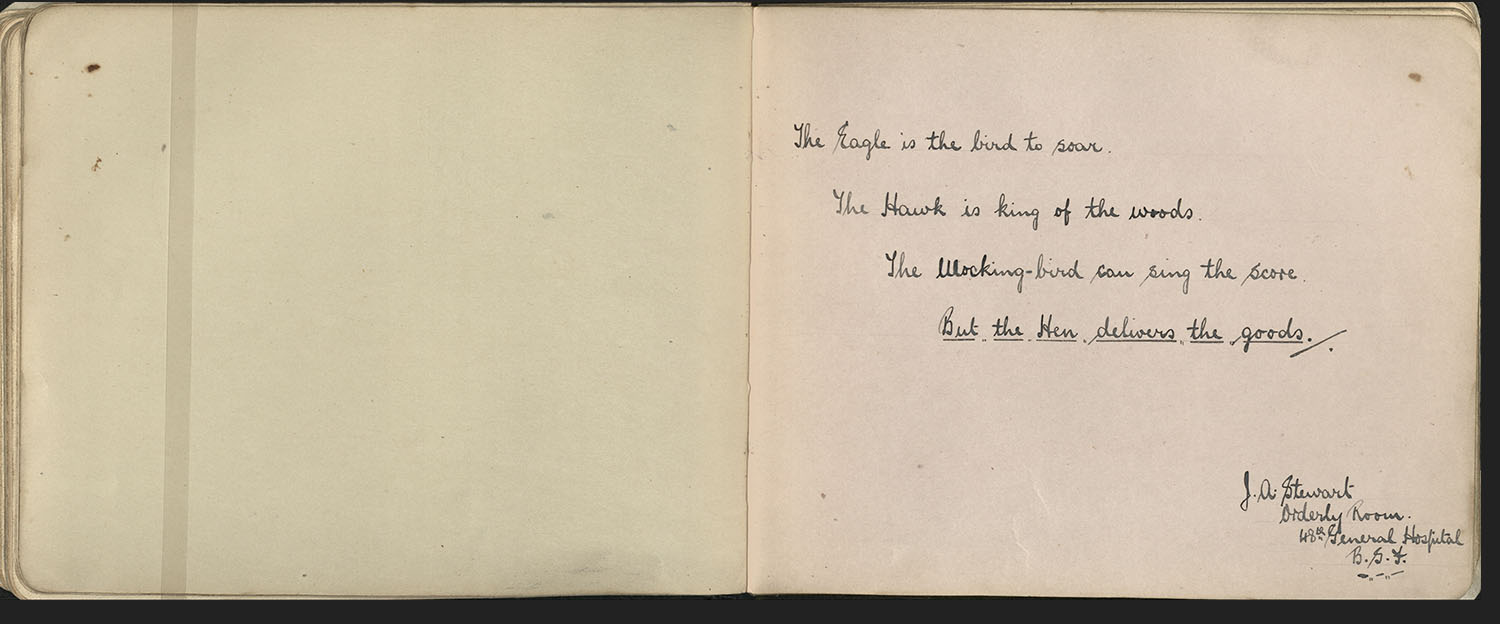

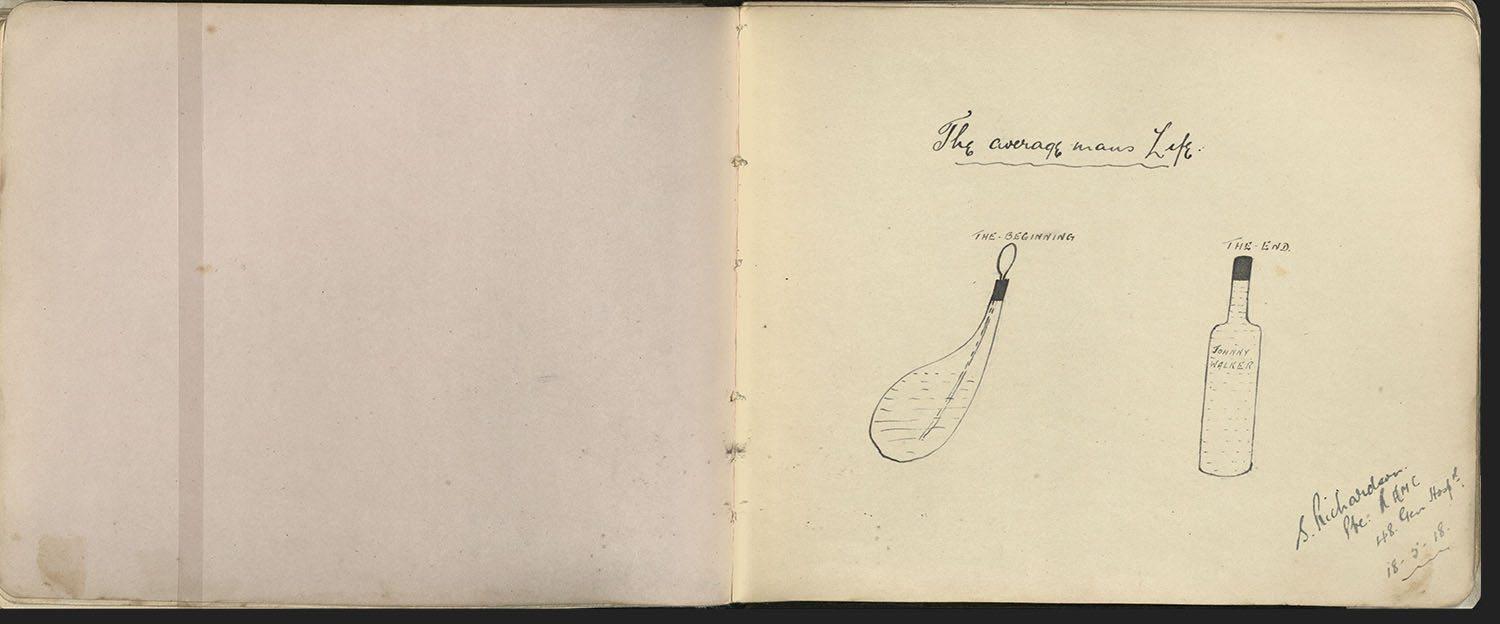

We know from her scrapbook that Akehurst was at Somerville by Christmas 1915. Whilst here she was a theatre nurse as well as being in charge of a small ward. At the time she started the hospital admitted every rank. Eventually, due to the college having private rooms and a large dining hall the rooms became allocated solely to officers. We can see this reflected in those who were signing Akehurst’s scrapbook – Private and Lance Corporals sign in early 1916, but by the end of the year only Lieutenants and Captains are leaving her messages.

Background image: 'World War I: Third Southern General Hospital, Oxford, extension in the Masonic Buildings.' by Walter E. Spradbery. Credit: Wellcome Collection. CC BY

Officers are requested not to throw custard at the walls.

Somerville

Somerville was an all-women’s college. The arrival of convalescing soldiers caused an upheaval. Somervillians were evacuated to near by Oriel College and shared with the few non-servicemen male undergraduates still in residence there. Brittain recalls it meant many of the female students had to live in male accommodation for the first time. It was not trusted that students could resist ‘khaki-fever’. Women Patrols were set up by older students and professors to deter immorality. Somerville library was off limits for the men but this photo shows them sitting in the sheltered loggia during their convalescence. We have no photos of Akehurst – perhaps she is one of the nurses we can see here? Or perhaps she is in the photo of the grounds? In this image we can see how the patients of Somerville were used to the fresh air. In the background you can see the tents that were erected in the gardens to maximise the accommodation. Whilst there the patients had some entertainment. The senior Common Room became the Billiard Room. The scrapbook Akehurst handed round would also have been a welcome reprieve for the men, who would have had little to do whilst recovering.

Good old Somerville.

If you know a better hole

Go to it

This quote is not as rude as it seems, but rather a play on the popular ‘Old Bill’ cartoon. Old Bill was a moustachioed officer whose grumpy take on the war was a hit with the British public. The cartoon the quote is referring to shows Old Bill in a trench with another soldier telling him "if you knows of a better ‘ole go to it."

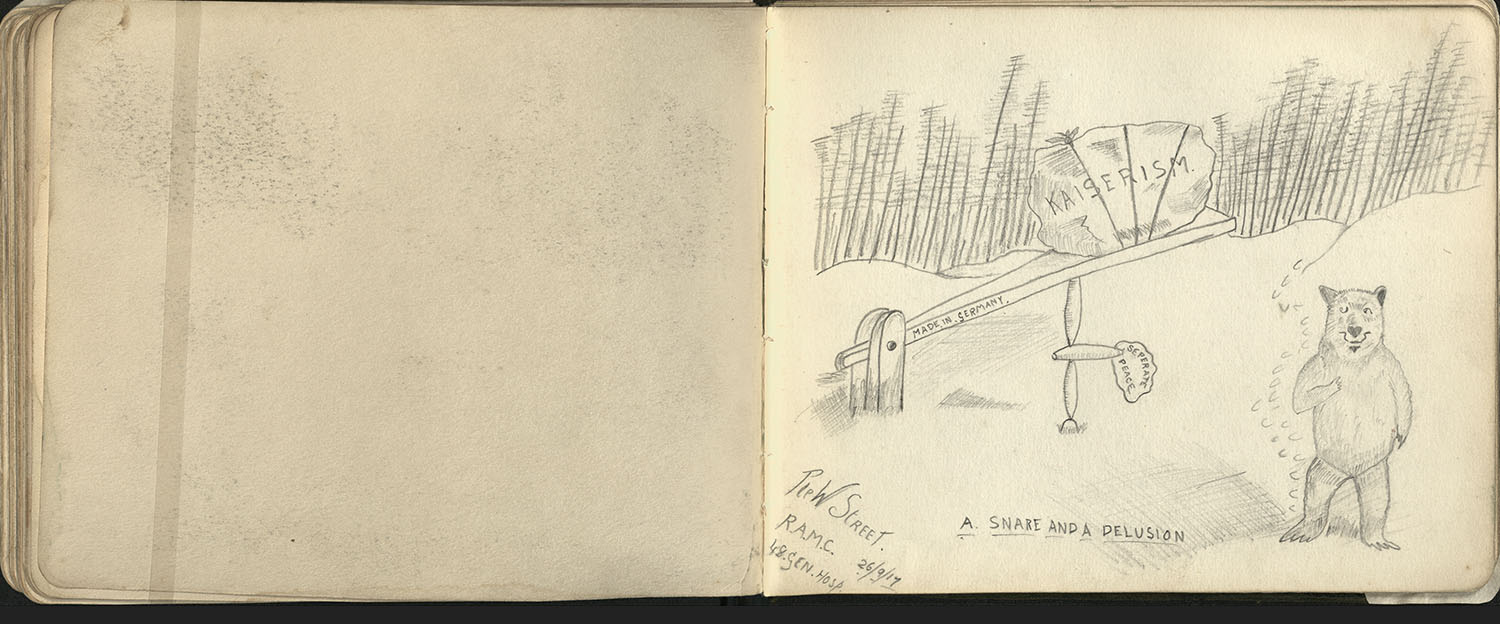

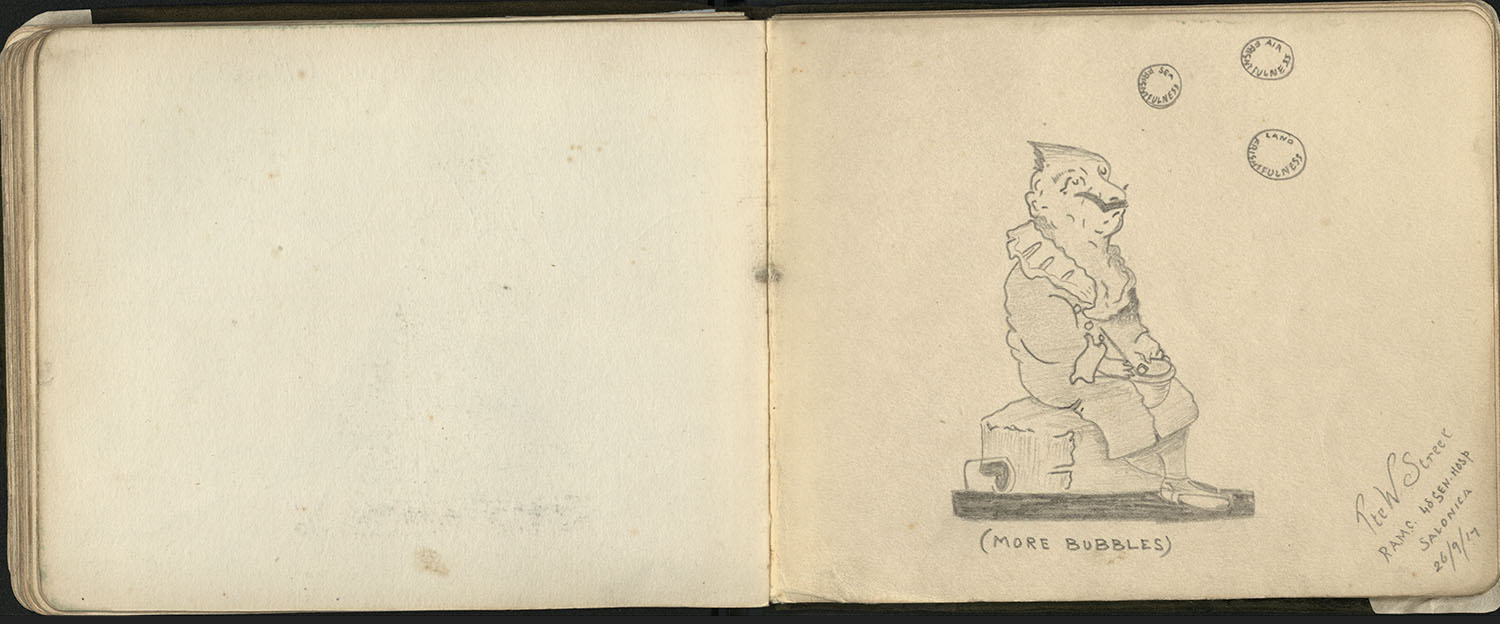

Bruce Bairnsfather, the man behind the cartoon, also inspired other illustrators in our scrapbooks. Three of his pictures can be seen copied out in Florence Blythe-Brown’s scrapbook, one of which is on the right.

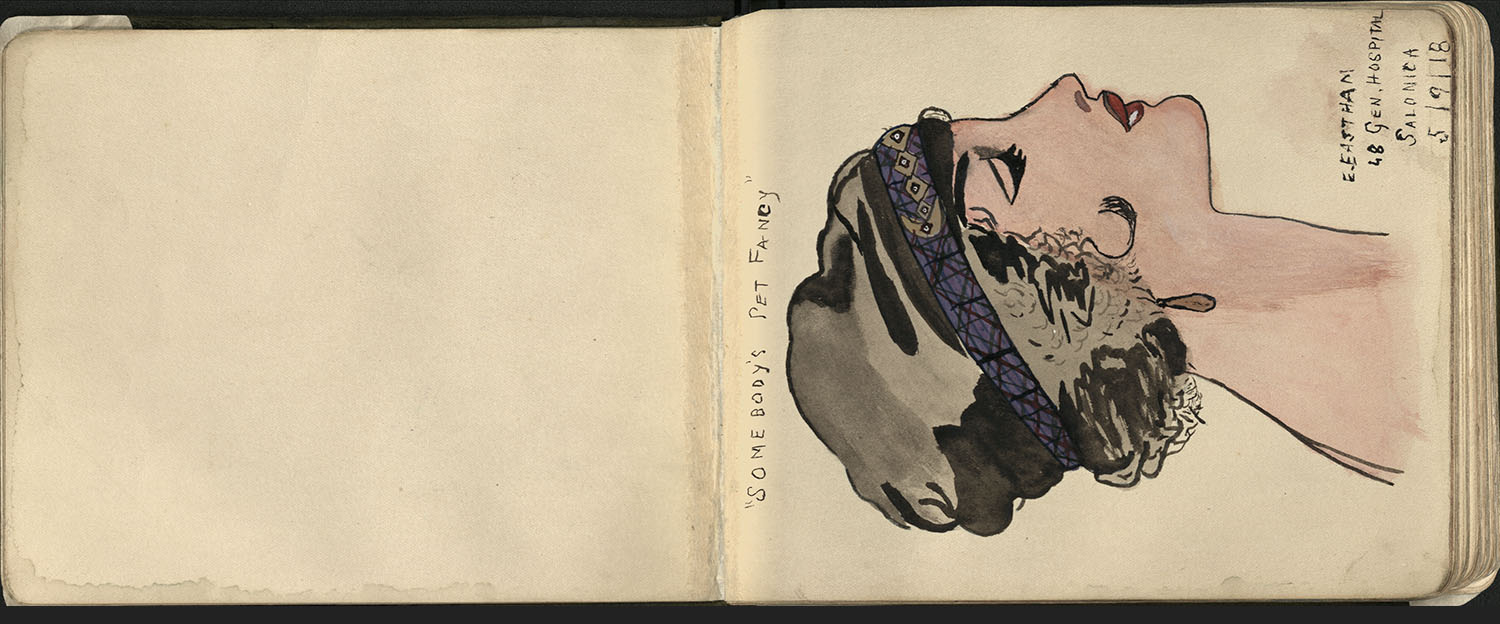

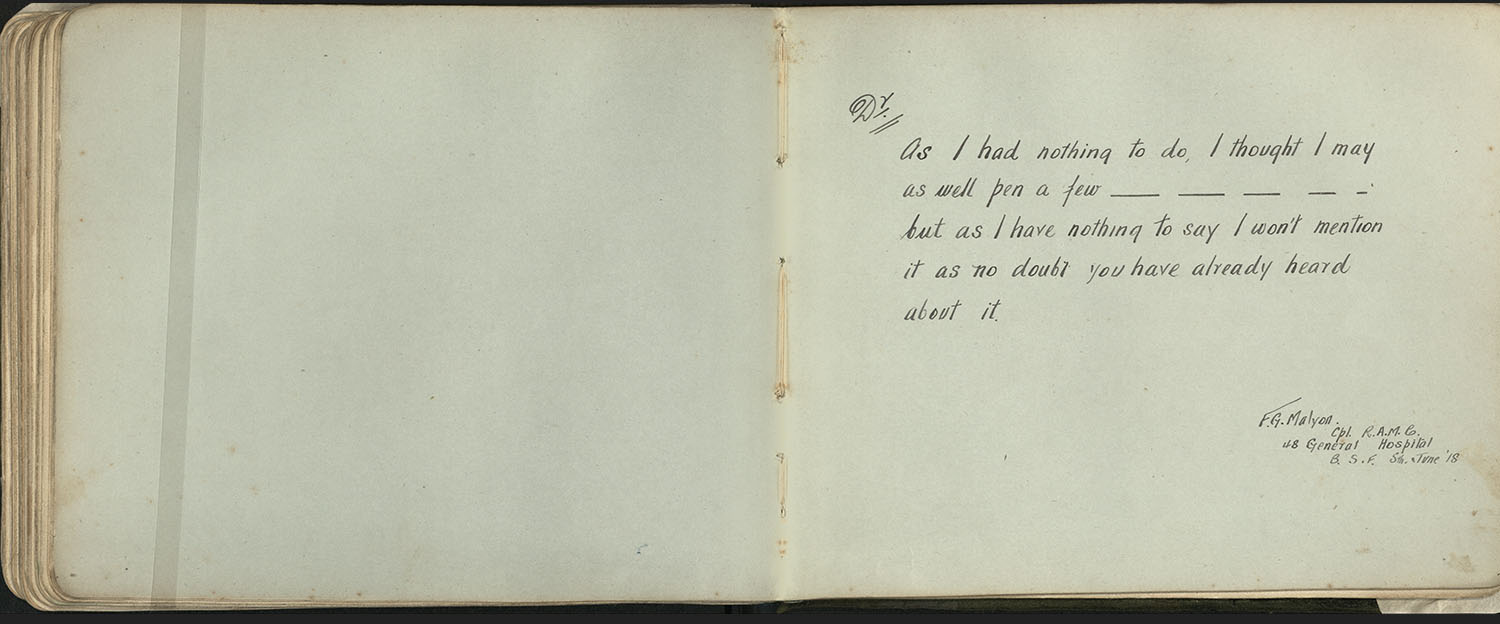

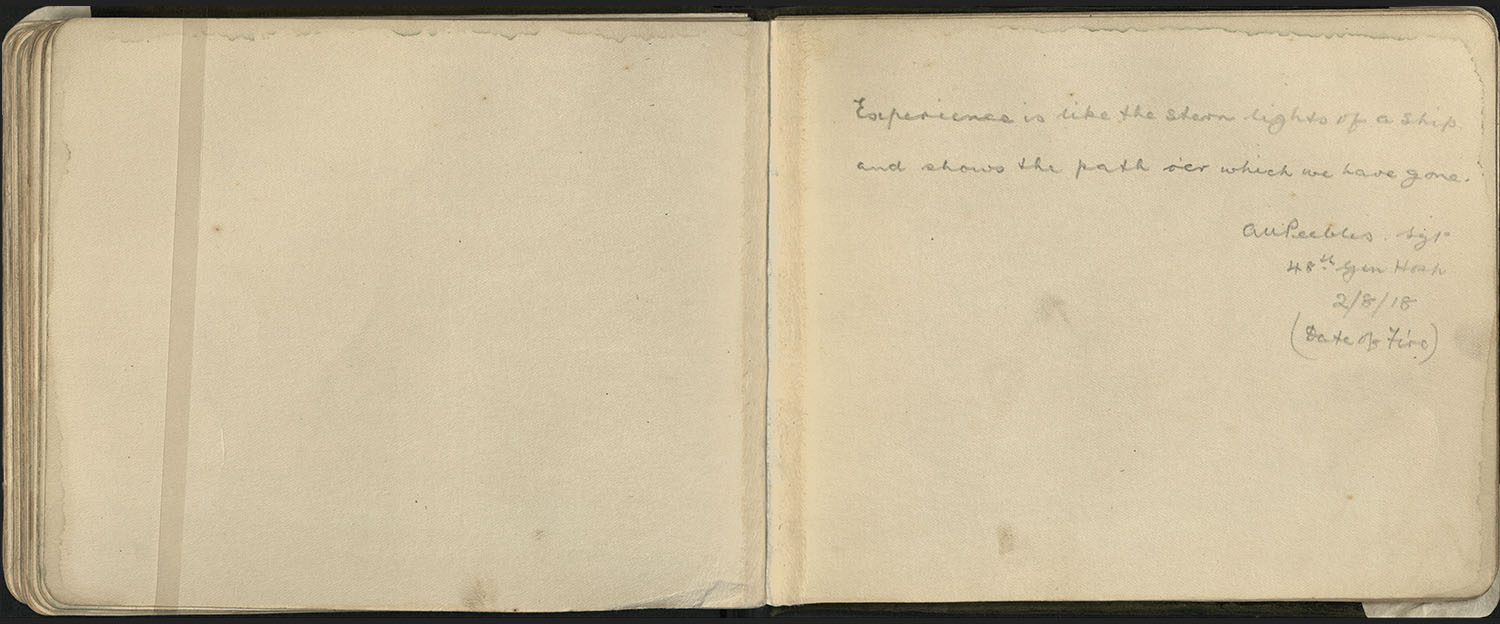

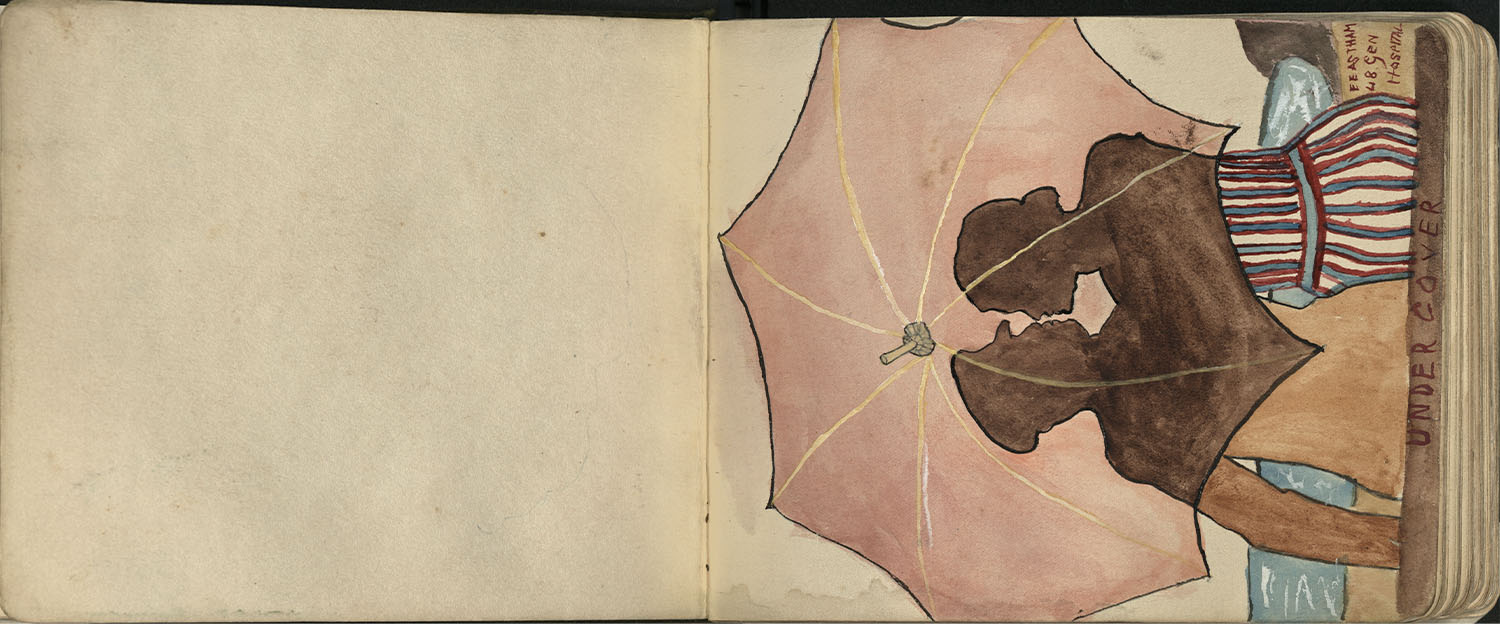

Scrapbook

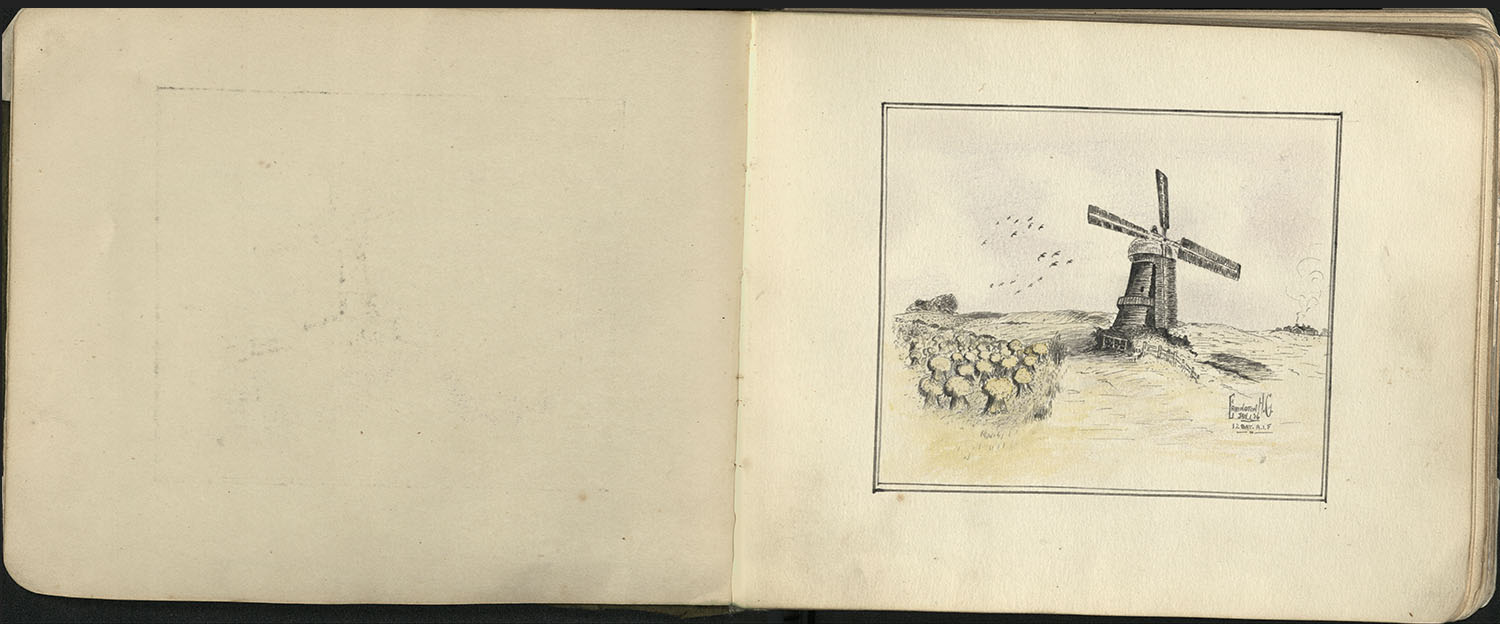

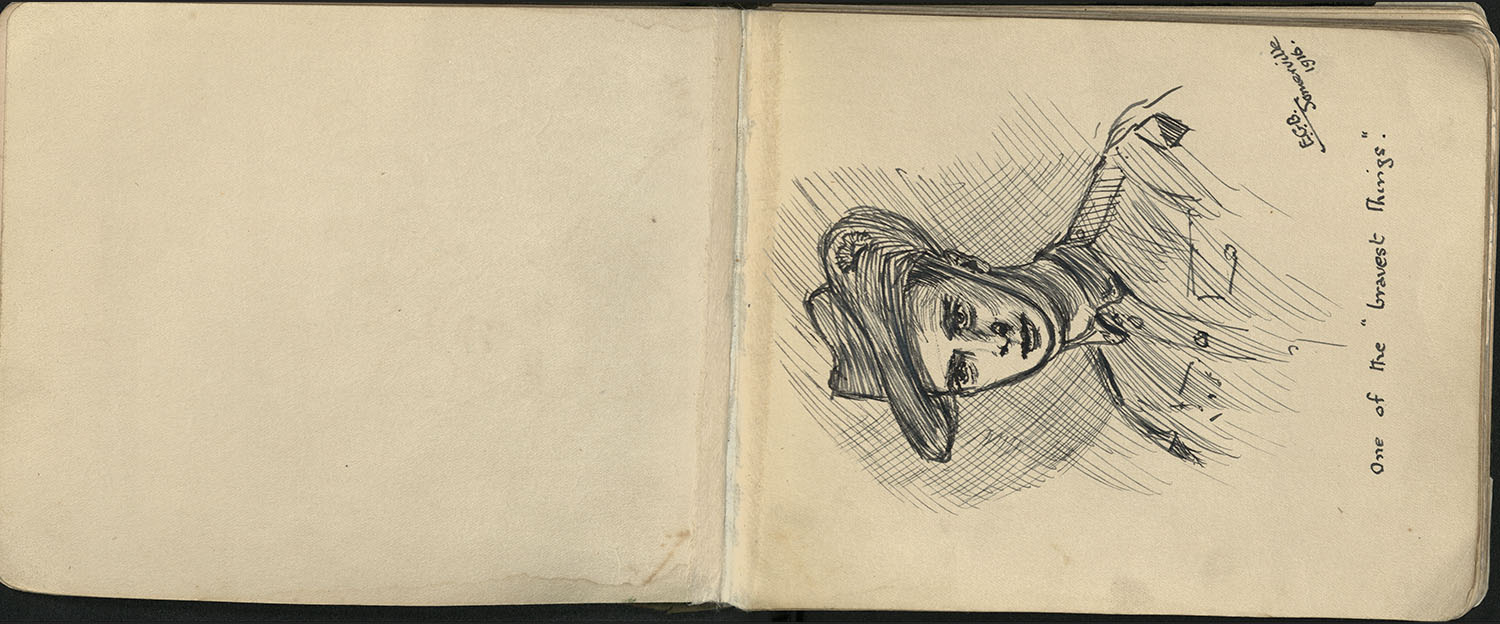

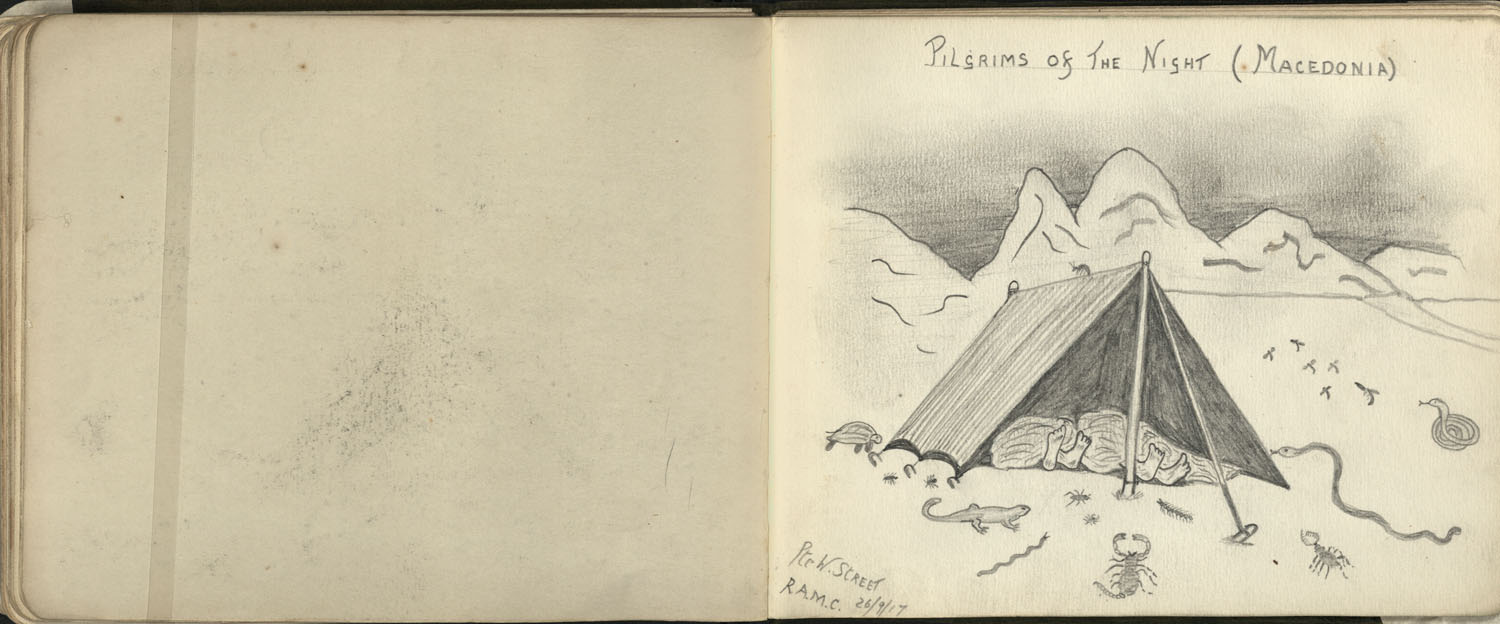

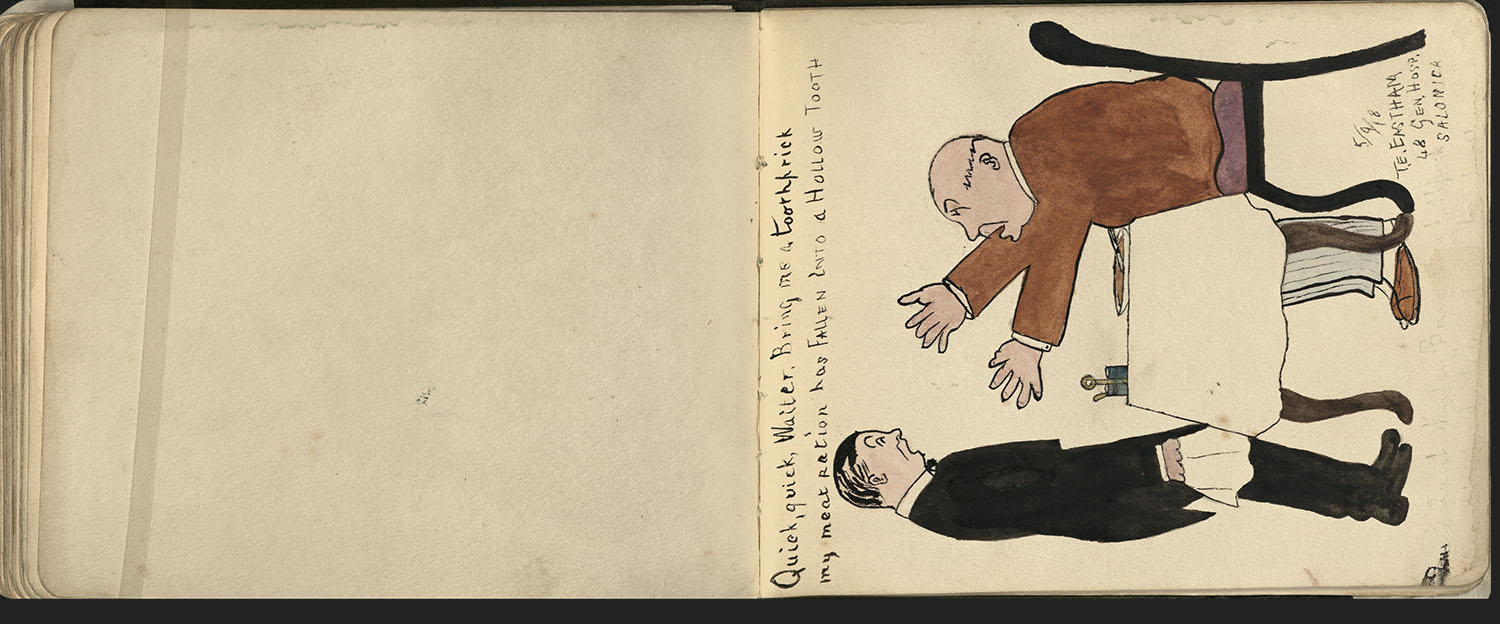

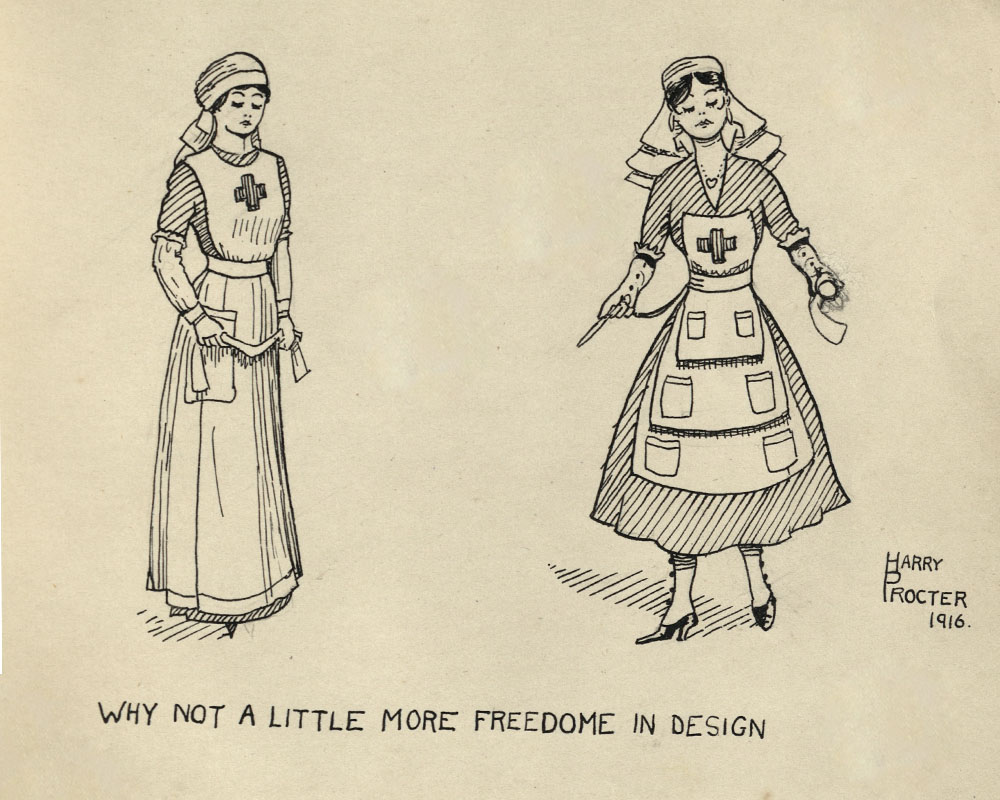

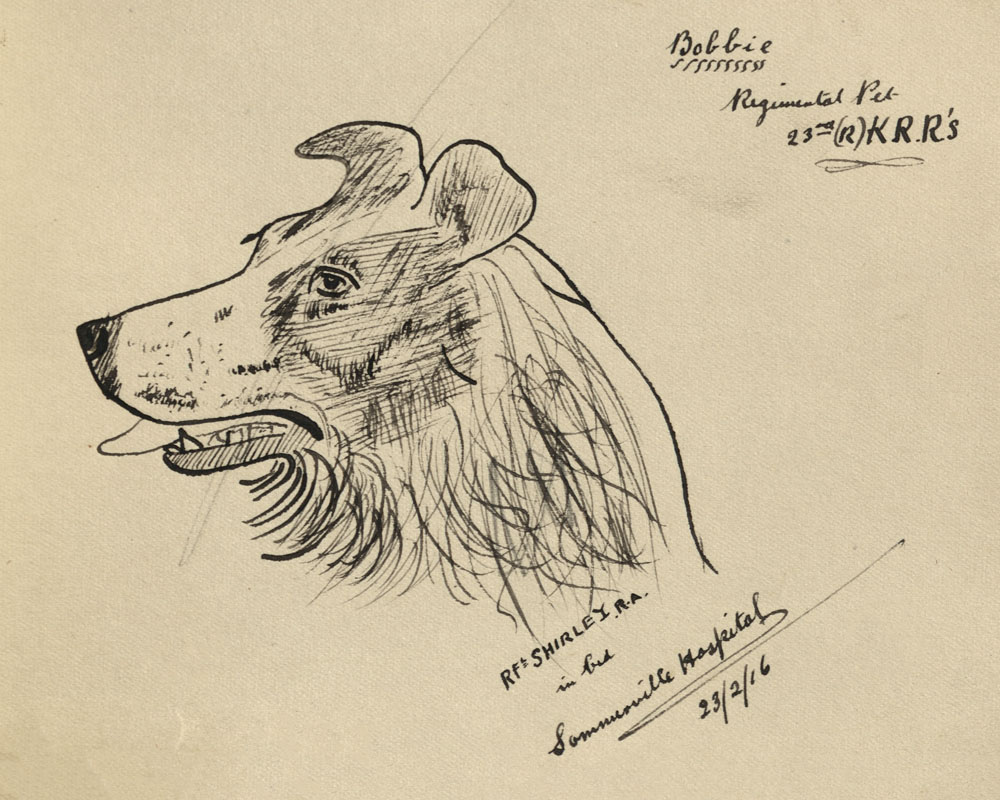

The scrapbooks are filled with patients distracting themselves. Rifler Shirley R.A. drew his regimental pet, Bobbie, taking care to mention the fact he was in bed whilst he did it. Regimental pets were very popular in the First World War, and were thought to improve morale. They were not used in action, but were mascots. It is likely that Bobbie was an unofficial mascot of Rifler Shirley’s regiment – the King's Royal Rifle Corps – as he is not on any official mascot lists. Another illustration of a dog shows us that the patients had access to paint. Clearly the nurses understood the importance of keeping people occupied.

Others choose to depict their opinions of the war. One soldier, J. Evie Smith, was probably injured at the battle of the Somme. His drawing, inked a month after the push, is clearly in reaction to the failure of the Allies strategy. The battle of the Somme is perhaps the most famous battle of the First World War due to the heavy losses received there. Of the three million men who fought, over one million men were wounded or killed, making it one of the bloodiest battles in human history. It took place between 1 July and 18 November 1916.

During this time, Siegfried Sassoon was taken into Somerville with a case of ‘trench fever’. Not until the end of the war was it realised that lice in the trenches were the cause of the widespread fever. Sassoon wrote about Somerville:

To be lying in a little white-walled room, looking through the open window on to a College lawn, was for the first few days very much like Paradise.

In a hospital capacity of around 260 beds it's likely Sassoon and Akehurst will have encountered one another. In the next year he would publically criticise the war and be sent to Craiglockhart War Hospital, to be treated for shell shock. It was here he met Wilfred Owen and encouraged him in his poetry.

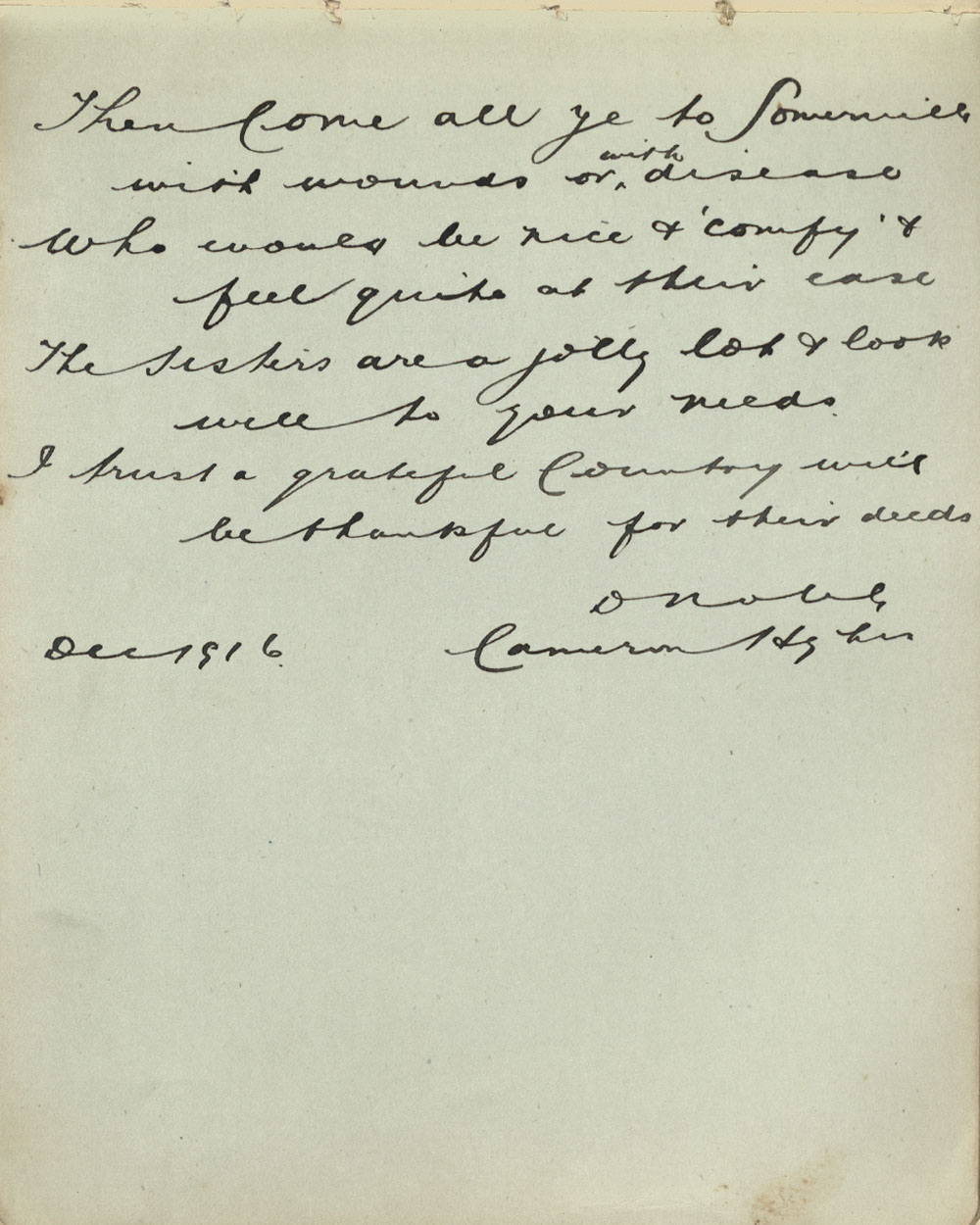

Then come all ye to Somerville

with wounds or with disease

Who would be nice & ‘comfy’ &

feel quite at their ease

The Sisters are a jolly lot & look

well to your needs.

I trust a grateful Country will

be thankful for their deeds.D Noble

Cameron Hgdrs

Dec 1916

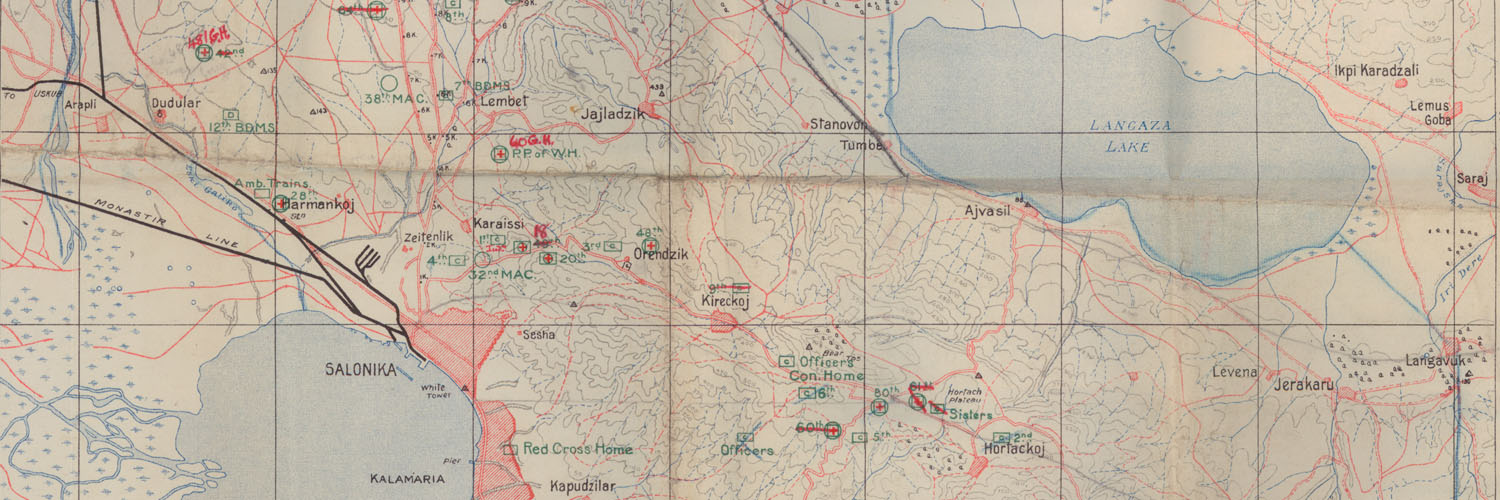

Salonica

On 30 March 1917, the principal Matron of Somerville Hospital, Miss Agnes Watt, recommended Akehurst for promotion. She was to join Miss Weale as an Assistant Matron at the 48th General Hospital based in Salonica.

On the same day she was examined and found to be in a fit state of health to undertake nursing duties in military hospitals overseas and she was vaccinated against Typhoid and paratyphoid on the 2 April 1917. Akehurst signed an agreement, witnessed by Agnes Watt in March 1917 to serve at home or abroad as a nurse in His Majesty’s Forces for as long as required during the present emergency.

The Salonica offensive had started at the beginning of that month, with half a million allied troops facing Bulgarian Army and German, Austro-Hungarian and Turkish units. In April the initial attack failed with major losses, and the offensive was suspended on 21 May.

For Akehurst the first major struggle was to get to Salonica. In February 1917 Germany had introduced unrestricted submarine warfare. The ship Akehurst had departed on 10 April was torpedoed. She and her companions returned to England and set off again nine days later. This time their journey was uninterrupted.

By the time Akehurst arrived in the 48th General Hospital its 1,040 beds would have been full, not only with wounded soldiers but those who were ill. In Salonica malaria became a massive problem, and caused more casualties for the Allies than the fighting.

Background image credit: McMaster University

48th General Hospital

Illness

In July 1917 Akehurst's mother, Margaret Akehurst, received a letter informing her that Akehurst had fallen ill. Unsure of how ill her daughter was she enlisted the help of a friend to write to the matron in chief of the hospital, who had no further information to give her. From Akehurst's active service form we can see that she was admitted to hospital in June, seriously ill with dysentery. She would spend the next year alternating between being a nurse and patient.

Akehurst stayed in Salonica until 1919. Her discharge papers record her as being a good organiser, a very capable ward manager, a good theatre sister and a cheerful and loyal worker. She was also said to have been a helpful and enthusiastic assistant matron. Described as 'fit for general service' implies that by this time she had thankfully made a recovery from her illness of the previous year.

Buried in Akehurst's file in the National Archives is a small note 'Mentioned in Despatches'. Akehurst received this recognition for distinguished and gallant services from 1 October 1918 to 1 March 1919. It is a recognition of her bravery.

After the war

On 13 March 1919 Akehurst was officially demobilised. She had served for three years, 297 days.

Seemingly not enough for Akehurst, she wrote to her Matron in Chief of her disappointment to have left Salonika. She mentions that many of the sisters went on to active service in Russia and asks to be sent there too. This request was denied. Instead Akehurst took a post as assistant matron in a maternity hospital in Bermondsey.

Almost exactly a year later Sidney Browne, Matron in Chief, wrote to thank her for her good service during the war. She said “your work has been excellent and has been fully appreciated by all those under whom you have served”.

In 1925 Akehurst was still a reserve member of TANs. This changed when she decided to get married. She wrote to inform the Matron that she had decided to get married and that she felt “you will not want to be bothered with me any more.” She was sorry for any inconvenience but she would like to continue to be a Territorial Nurse if possible. Dame Maud McCarthy wrote back to inform her that she would no longer be able to remain as an enrolled member after marriage. She explained that in peacetime, married members were not eligible for retention in the Service, but should a national emergency arise her application would be considered.

With this sorted out, Akehurst married Harry Bateup in her home town of Brighton. She was 48 and he was 57. The new Mrs Bateup could not continue to nurse even domestically as a married woman, so her nursing career came to an end.

We know that Mr and Mrs Bateup lived into old age, spending over 20 years together in Brighton. Mr Bateup died in 1948 aged 80, and Mrs Bateup, nee Akehurst, died on 13 March 1956 aged 79.

Images

'World War I: Third Southern General Hospital, Oxford, extension in the Masonic Buildings.' by Walter E. Spradbery. Credit: Wellcome Collection. CC BY

Images of Somerville, Third General Hospital courtesy of the Principal and Fellows of Somerville College, Oxford

Salonika Map courtesy of McMaster University, http://digitalarchive.mcmaster.ca/islandora/object/macrepo%3A4141 CC BY

Medal images courtesy of the RCN archive

References

Allen, T. (2014). Bruce Bairnsfather ww1, Postcards Picture Postcards from the Great War, 1914-1918 [online] https://www.worldwar1postcards.com/bruce-bainsfather.php [Accessed 11 Dec. 2017].

Brittain, V. (1933). Testament of Youth. Penguin books, p.146-150.

Imperial War Museums. British First World War Service Medals. [online] Available at: https://www.iwm.org.uk/history/first-world-war-service-medals [Accessed 11 Dec. 2017].

August 1916: Siegfried Sassoon at the 3rd Southern General, Somerville and the Great War. (2016) [online] Available at: The First World War - Somerville College Oxford [Accessed 11 Mar. 2025].

Somerville Hospital – Then and Now, Somerville College Oxford. [online] Available at: https://www.some.ox.ac.uk/news/somerville-hospital-then-and-now/[Accessed 11 Dec. 2017].