There are 7.6 million people living with heart and circulatory disease in the UK, says the British Heart Foundation.

But with 80% of cardiovascular disease (CVD) cases being preventable, nursing staff can play a key role in reducing their patients’ risks, says CVD nurse specialist Michaela Nuttall. “We need to think about how we can help people to change,” says Michaela, a member of the RCN’s Public Health Forum. “It’s about going back to basics – stopping smoking, eating a healthier diet, controlling our weight, being more active, and moderating alcohol.”

What is cardiovascular disease?

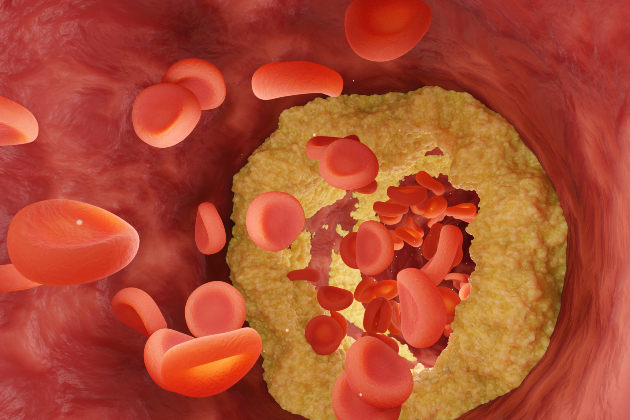

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is an umbrella term for conditions affecting the heart and blood vessels. It’s associated with atherosclerosis – a build-up of fatty deposits, known as plaques, inside the arteries, which cause them to harden and narrow, restricting blood flow. It can also come with an increased risk of thrombosis – blood clots that can lead to further health issues.

NICE lists 4 main types of CVD:

- Coronary heart disease – when the heart muscle’s supply of oxygen-rich blood is blocked or reduced. This can lead to angina, heart attacks and heart failure.

- Strokes and transient ischaemic attacks (TIAs), also known as ‘mini strokes’ – when a blockage or supply issue cuts off blood supply to part of the brain.

- Peripheral arterial disease – caused by blockages in arteries carrying blood to the limbs, usually the legs.

- Aortic diseases – a group of conditions affecting the aorta, the largest blood vessel in the body.

Michaela suggests thinking of vascular dementia, chronic kidney disease, and erectile dysfunction as types of CVD too. “We’re always looking for early diagnosis, because that means earlier treatment and improved outcomes for patients,” she says.

Making a difference

Nursing for more than three decades, Michaela’s career includes running her own training company, working for a public health charity, and sitting on committees and working parties linked with cardiovascular health.

She believes that nursing staff working in all kinds of settings have the chance to make a difference. “Be curious,” says Michaela. “Ask your patients if they have any health concerns or have considered different lifestyle changes. There are all kinds of ways we can have a positive impact, without telling people what they should and shouldn’t be doing.

CVD facts and figures

- CVD accounts for ¼ of all deaths in the UK, says NICE, although rates have fallen significantly since the late 1970s – from 914 per 100,000 in 1979, to 251 in 2016.

- Socioeconomic status is an important risk factor. “Death from CVD is 3 times higher among people in the most deprived communities, compared to those that live in the most affluent,” says NICE.

- Other risk factors include: increasing age; a family history of CVD; and ethnic background, with those of South Asian or sub-Saharan African origin having higher risks.

- CVD is the biggest killer of women in the UK, but it can be under-recognised and under-treated, says the Health Research Institute.

- Several comorbidities also increase the risks of CVD. These include: hypertension; diabetes; atrial fibrillation; rheumatoid arthritis, lupus and other systemic inflammatory disorders; periodontitis; and dyslipidaemia – blood lipid levels, when bad cholesterol is too high or good cholesterol too low.

For those patients already diagnosed with heart problems or who may be recovering from a heart attack, nursing staff can also be an invaluable source of support as they come to terms with lifelong treatment. “Patients may suddenly have to take four or more tablets every day,” says Michaela. “And while the pills are helping them to live longer, they may not necessarily feel any better, which can make people think, what’s the point.”

Nursing staff can boost compliance by explaining to patients what each tablet is for, how they work, and helping to manage any adverse side-effects, she says.

“If patients understand all this, they’re more likely to take them,” says Michaela. “Health literacy is key in people being able to manage their own conditions. As nursing staff, we can help by saying, show me what you do. That’s where you can get to grips with what’s happening in practice and whether your patient is taking their tablets in the right way.”

Top tips to improve your practice

- Pay attention to what your patients tell you, says Michaela. “Really listen. For instance, they might say they’re having pain in their legs when walking, or they feel more tired than usual,” she says. “Don’t just dismiss symptoms, but think about what it could be. And if anything doesn’t feel right, act upon it.”

- Ask about family history. “If your patient tells you their dad had a heart attack in his fifties, that should raise your alert level,” says Michaela.

- Make sure your blood pressure measuring technique is good and you act on the results. “We need to put people on diagnostic pathways, as needed, supporting them to lower their blood pressure,” says Michaela.

- Familiarise yourself with the different symptoms of a heart attack, especially for women. “Most of what we know from research is predominantly based on white men, and what we’re seeing with women is that it doesn’t quite fit,” says Michaela. For example, pain may be in arms, shoulders, back or throat and may not be sharp, but more of a dull ache, perhaps a feeling tightness or squeezing or breathlessness, or even dizziness, nausea, or a sense of anxiety.

- The focus should be on prevention wherever possible, says Michaela. “Disease takes years to build up,” she says. “If we wait for symptoms, we’re way down the line. Ideally, we need to intervene much earlier.”