Our new exhibition explores how expectations of nurses have evolved over 150 years

In Cowdray Hall, inside the RCN’s London headquarters, three stained glass windows illustrate the emotions associated with nursing 100 years ago: faith, fortitude and love. But in 2020, have things changed?

Across the building, in the RCN Library and Heritage Centre, three new windows have just been unveiled. Created by artist Rachel Mulligan, with input from RCN members across the UK, these stained-glass artworks depict nursing today and how nurses touch people’s lives, from birth to death.

“The windows show the complexity of nursing: how the clinical and technical expertise of the nurse and the emotional side of nursing are not separate, but need to be considered all together,” says Sarah Chaney RCN Events and Exhibition Manager and Research Fellow at Queen Mary University of London (QMUL).

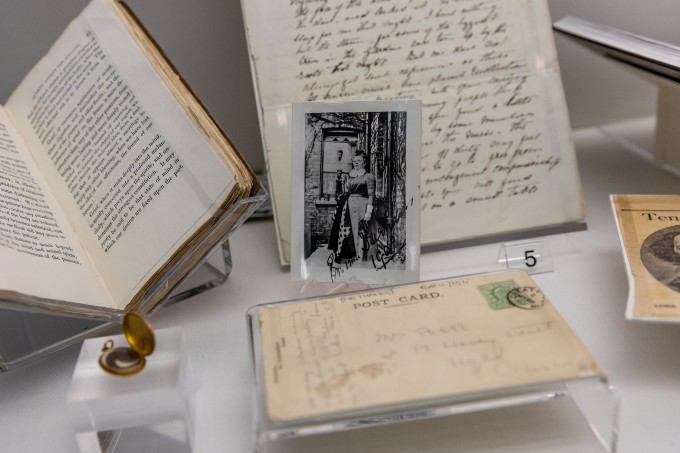

The new windows are part of the RCN’s latest exhibition, Who Cares? A History of Emotions in Nursing, which opened to the public in January. In it, Sarah and other researchers look at the place of emotions in nursing: what emotional qualities make a good nurse? Has that changed over time? And what about the emotional wellbeing of nurses?

“Through history, one of the biggest problems in nursing is that the emotional side has just been assumed, either because you're a woman or because you're a caring person, and not really acknowledged in terms of training, support or pay,” Sarah explains. “It's an invisible part of the work, which we wanted to recognise.”

The exhibition is split into six emotional themes – birth, death, romance, faith, war and protest – explored through artefacts from the RCN Archive and other collections. It draws on new research from QMUL’s Centre for the History of the Emotions, funded by the Wellcome Trust, and spans 150 years, from the era of Florence Nightingale to the present day.

“Emotions and the way they're expressed and understood have changed through the history of nursing,” Sarah says. “This has had a huge impact on how nursing's been understood over the years.”

In the late 19th and early 20th century, nurses were expected to be “calm, quiet and orderly”. The idea of showing “compassion” to patients was rarely mentioned. But that’s shifted as our society and the role of nursing has changed. Now, the relationship between nurse and patient is more of a priority, which, says Sarah: “can sometimes lead to unfair pressure on nurses”.

This message came out clearly during research workshops with RCN members. “A primary theme was the conflicts between expectations and time and capacity, and there was a lot of talk about wellbeing for nurses and finding ways to manage your own emotions,” Sarah says.

They weren’t available for the workshops, but the voices of nurses from the 19th century come through in guidance books and textbooks. This was the start of an era when the role and expectations within nursing were finally being defined.

“Much of the focus then was around order,” says Sarah. “The nurse is being seen as someone who's responsible for maintaining order, but also themselves being obedient. There's a lot of emphasis on the nurse being quiet, obedient and loyal. In the later 19th century… introductory lectures in the nursing schools were saying that loyalty to your hospital is paramount.”

Upper-class “lady” nurse leaders at the time, such as Florence Nightingale and Ethel Bedford Fenwick, often described the ideal nurse in class-based terms. They wanted to move away from what they believed to be a negative stereotype of nursing, based on Charles Dickens’ drunken, dishevelled, working-class nurse character Sarah Gamp. “They tended to assume that if nurses behaved a bit more like ladies, then they would be better nurses,” Sarah explains. “Nightingale would emphasise punctuality in her nurses and their appearance – looking clean, orderly and tidy.”

Religion also played a role. Florence Nightingale’s bible is on display in the exhibition, highlighting a common 19th and early 20th-century belief that nursing was a calling, with nurses expected to consider their patients’ spiritual as much as their physical wellbeing. “Fenwick wrote an article after the introduction of registration, claiming that someone who sees nursing as ‘just a job’ cannot be as good a nurse because they are not tending to the souls of their patients,” Sarah says.

The First World War began to shift the way nursing was seen and the qualities that nurses were expected to have. Courage became a highly prized emotion and a new public figure set the tone for nurses across the country. “Edith Cavell certainly played a big part in perceptions of nursing,” Sarah says. “She was celebrated for being completely calm, stoic and keeping a stiff upper lip throughout – essentially for not showing emotion, rather than for having a particular set of emotions.”

In the 1920s, nursing textbooks continued to emphasise the idea that nurses should hide their emotions from patients and stay calm at all times, while always being aware of their patients’ emotions.

Sarah’s own research has focused on the interwar period, from 1922 to 1936, looking at the way the General Nursing Council tried to “purify the profession” by striking nurses from the new register. Nurses’ private lives were scrutinised, with illegitimate children, divorces or rumoured affairs providing possible reason for being struck off. “They saw a nurses’ sexual indiscretion as putting a bad light on the nursing profession,” Sarah says.

There was a huge drive to recruit young women to the newly formed NHS following the Second World War. With this, came another shift in the emotions associated with the profession. “There was a renewed emphasis on nursing and motherhood, that nursing comes out of maternal qualities, that it's something that will prepare you for marriage, or that you could continue because marriage will help you become a better nurse,” Sarah explains. “Oddly, this took gender stereotypes in nursing back several decades.”

Soon, the need for NHS efficiency changed the role of nursing staff. The importance of calmly executed clinical practice and solid practical skills overtook the visions of maternal instinct found in post-war recruitment videos and pamphlets. But by the 1980s, the nurse's relationship with patients was centred once more. Rather than a familial bond though, the nurse came to be seen as the patient’s advocate, negotiating between the clinical and emotional needs of each person.

It’s only in recent years that the emotional needs of nurses themselves have been highlighted. The toll of dealing with life and death situations while remaining strong under tough working conditions is becoming clearer. Perhaps over the next 150 years, the emotions nurses feel will become just as crucial as those they’ve been expected to perform.

Words by Rachael Healy. Pictures by Justine Desmond