On 22 June 1948, the HMT Empire Windrush arrived in Essex, carrying hundreds of passengers from the Caribbean to help fill post-war workforce shortages. Just two weeks later, on 5 July, the National Health Service was created.

Many Windrush passengers took up roles in the NHS, including as nursing staff. Those first NHS employees faced overt racism and discrimination, and their qualifications weren’t recognised. But despite these hardships, they committed to caring for British citizens, forming a crucial part of our health service.

Since then, people from around the world have continued to contribute tirelessly to the NHS, making it a diverse and unique national treasure. But without help from the Windrush generation of nurses, the NHS as we know it couldn’t have survived.

Here are some of their stories.

It remains vital to remember and honour those from the Windrush generation and everything they sacrificed

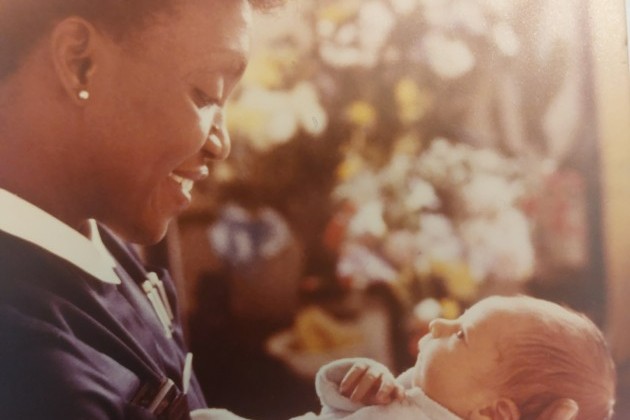

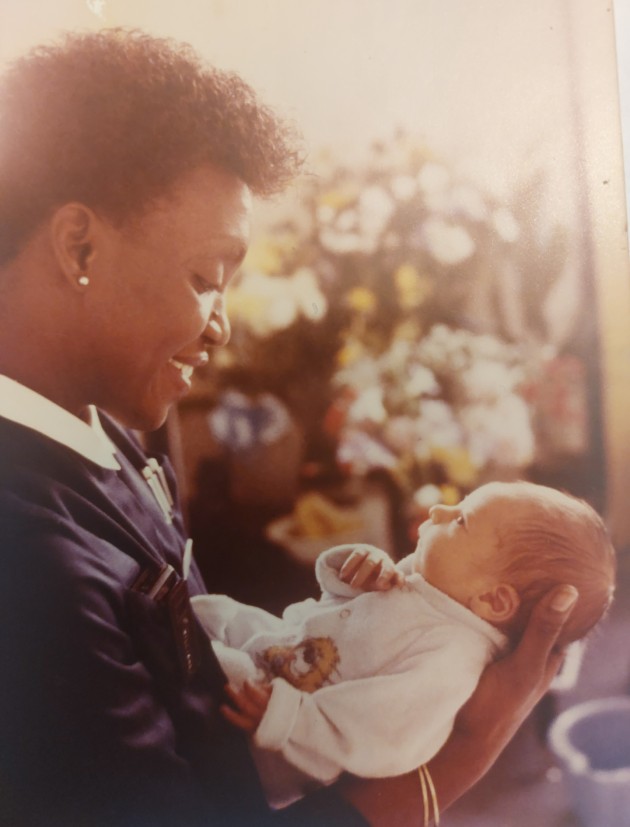

Yvonne and Dionne

When Yvonne Daniel came to England from Trinidad in 1961 she was “looking for an adventure”. A qualified nurse already, she responded to the call for workers to staff the fledgling NHS and travelled thousands of miles from the only place she’d ever known. She hoped she’d have some new experiences and benefit from greater career opportunities.

Reflecting back on it now, 62 years later, her niece Dionne – also a nurse who came from Trinidad to work for the NHS in 1998 – admits that, although there was some enjoyment and happiness, a lot of it was “a real struggle”.

“My Aunt had some, let’s say, interesting experiences,” Dionne recounts. “She always tells the story of her first roommate who asked her where her grass skirt was when she’d finished unpacking, genuinely perplexed that she didn’t have one.”

Ignorance and racism plagued Yvonne’s daily life in England. From patients refusing to be nursed by her and other Caribbean colleagues, to people moving out of the area where she bought her first house. She even changed denomination to Mormon after trying to attend Catholic church and not being welcome there.

This was of course, as Dionne points out, at a time when you couldn’t just hop on a plane and return home. It was an arduous and expensive journey – “you couldn’t just say, OK, I’ve had enough now”. As time went by, Yvonne met her husband, had children and settled.

“Some aspects of it she enjoyed, it wasn’t all doom and gloom. But there are some parts of it that still sit with her. That to me is a shame.”

I’ll always remember my aunt’s generation and what they’ve endured

Yvonne worked in the NHS for over 40 years until ill health forced her to retire. Even then she continued to contribute tirelessly to the community, running crochet classes at her local GP surgery, volunteering for Oxfam, and remaining active in her church.

“I don’t think she regrets coming over here, she has her children and her grandchildren now, but I’m not sure she would do it all over again, and she wouldn’t advise anyone else to come here.”

Indeed, when Dionne decided to move to Eastbourne from Trinidad in the 90s, Yvonne tried to talk her out of it.

All the difficulties she’d faced, combined with the fact “she felt she’d never reached her full potential in the NHS” due to discrimination and systemic racism – becoming a ward sister only late in her career, made her fear for her niece’s experience.

“For me, it was a different time,” Dionne says. “There were still challenges – a lot of tears and a lot of trauma – some that almost destroyed my career if I’m honest, but I’m still standing. We were able to fight back a bit more. I’ve also had very good people in my corner and felt supported.”

Dionne has battled for a career that has gone from strength to strength, admitting she had to be “more creative” to continue advancing. But each time she was promoted, Yvonne cried, so happy for and proud of her niece.

“I’m so aware that I’m walking on the shoulders of my auntie. She was and still is an inspiration to me. She’s in a nursing home now, giving them hell! She’s a fighter.

“I’ll always be a voice against discrimination and poor practice and how the NHS in itself works. And I’ll always remember my aunt’s generation and what they’ve endured. Because we can never take for granted those experiences. It wasn’t that long ago and it feels like people have forgotten it already.”

I’m so aware that I’m walking on the shoulders of my auntie

Sadly, Dionne says there is still widespread, systemic racial discrimination in the NHS with “lots of work to be done and conversations to keep having”. It remains vital to remember and honour those from the Windrush generation and everything they sacrificed, she says.

“We mustn’t forget the contribution they made to the NHS,” Dionne reminds. “We mustn’t forget their struggles and that some of these struggles continue.

“I hope that as time moves on, the next generation don’t have to put up with some of the things we did and that doors are opened.”

Windrush poem

Did we care for you as we should? Were we kind, are we good?

At RCN Congress 2023, nurse Carmel O’Boyle led a discussion about the Windrush generation of nursing staff and the huge part they played in the creation and early success of the NHS.

She started it by reading a poem she’d written, paying tribute to their skills, personal sacrifice and poor treatment.

Listen to it now:

Who are the Windrush generation?

The Windrush generation are people who arrived in the UK from Caribbean countries between 1948 and 1971, when British immigration laws changed.

Although not all Windrush generation migrants arrived on HMT Empire Windrush itself, the ship became a symbol of the wider mass-migration movement.

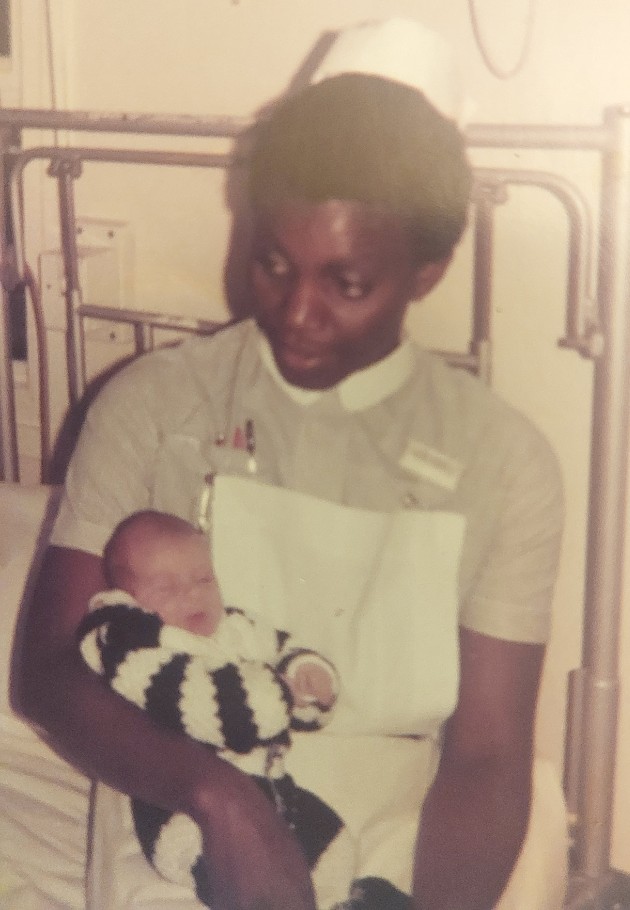

Allyson

Allyson Williams arrived in London on 16 May 1969 as a member of the Windrush generation. She was proud to have been invited, to gain high quality nurse training and be part of “helping rebuild the motherland”.

Allyson seized every opportunity she could, specialising in midwifery and women’s health, eventually becoming a senior midwife manager and then hospital deputy head. She was honoured with an MBE in 2002 for her outstanding services.

However, it was far from plain sailing. Here Allyson describes some of her early experiences and the struggles and racism she’s faced throughout her career in the NHS.

My mother was a nurse and I’d always wanted to be like her. She encouraged me to go to England saying it would be the best place for me to train. I decided to train at Whittington Hospital in London because I wanted to be in a big city and I’d been told they had a good reputation for looking after international recruits.

It was very frightening coming over. I really had no idea what to expect. But in my training set, there were 30 of us and 16 were from Trinidad. None of us knew each other beforehand though. It was the strangest thing. I still have very strong friendships from that time.

When I arrived, I was so surprised by London. I thought it was so drab and so ugly looking. I’d never seen terraced houses before and kept asking: “Is this all one house?” When I realised what it was, I couldn’t believe it and thought: how do people live with houses stuck to each other? In the Caribbean, there’s so much land and space. The way of life was quite a culture shock.

The other thing that completely flawed me was the overt racism. Trinidad was so multicultural. Judy my best friend was White – blonde with blue eyes. There was no animosity in the way we lived with each other at all. That’s how I remember it anyway.

When I came here, patients were slapping my hand away and screaming “don’t touch me” and “get your hands away, your blackness will rub off”. That was scary. You didn’t feel as though you were learning anything or doing anything positive to help them.

The racism was just continuous. I remember ringing my mother in tears after six months and saying: “I’m coming home, I can’t stand these people and how they behave.” But my mum said: “Racism is other people’s problem, not yours. You’ll just find a way to deal with it.”

One day, I suddenly had this ‘aha!’ moment on the ward. I stood up at the front and said loudly: “I am fed up of this abuse and the way you people treat me. I am 21 years old and I’ve been Black for 21 years. I know that I am Black and I have no problem being Black. So tell me something I don’t know.”

I noticed after that their attitudes started changing a little, they were a bit less aggressive. But mainly for me it gave me a real sense of peace and while the discrimination and racism persisted, right through my career, I never let it have the effect of making me feel inferior or frightened after that.

I was very glad to have stayed and raised my family in London to be honest. I don't know if anything that happened to me would have happened in Trinidad. I got my first degree and my Masters and other advanced training in midwifery. I became a strong advocate for women and their families in my care during my long career.

I also met my husband here. He was a fellow Trinidadian and we had the most amazing, wonderful marriage. He was a founder member and pioneer of the Notting Hill Carnival and we have continued this legacy for the last 40 years.

There is much work to be done. My friends who work in the NHS still report ongoing discrimination. Racism remains firmly embedded in the health service and most of it goes unchallenged.

I don't think the contribution of the Windrush generation is respected or recognised as it should be. This invaluable part of British history and the development of multicultural Britain should be taught in schools as standard, not just once a year during Black History Month. Education should go hand in hand with celebrating this generation.

There is much work to be done. Racism remains firmly embedded in the health service

Our ongoing fight for equality

Those from the Windrush generation represent just a fraction of the many internationally educated nursing staff who have come to work in the NHS over its 75-year history.

The NHS is now the biggest employer in Europe of people from a Black, Asian or minority ethnic background, making up more than 20% of the NHS workforce and representing more than 200 nationalities. Without the help of nurses and other medical staff from around the world, the NHS as we know it could not have survived.

Despite this, many of these people have faced challenges, from qualifications and culture changes to overt racism and a system that doesn’t allow equal opportunity.

The RCN aspires to be a world-class champion of equality, diversity, inclusion and human rights, providing workplace advice, support and representation to internationally educated nursing staff and fighting against any discrimination they may face.

Find out more about our diversity and inclusion work, as well as our award-winning cultural ambassador programme.

Read more: Migration, the NHS and the RCN