As a student nurse in the 1980s I often wondered why the ward sister always gave out the meals; why she thought this was such an important role?

Researching wartime nursing for over a decade has demonstrated to me how ignorant I was. Nutrition and the way we feed our patients is critical.

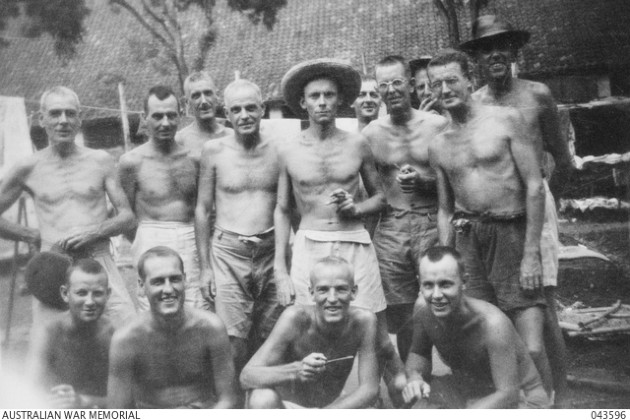

Nursing staff in South East Asia detained by Japanese armed forces in the Second World War became severely malnourished, yet went to considerable lengths to find food and nutrition for their patients. It was particularly challenging trying to feed those patients who couldn’t eat solid food or who had gastrointestinal issues.

Impact of war

On Christmas Day 1941, the British surrendered Hong Kong to the Japanese Imperial Army. Two months later, the Japanese took Singapore. Allied nationals not able to escape were interned – they were prisoners of war.

The last British women to be released did not find freedom until September 1945, four months after the end of the war in Europe. Those who were still living had been in captivity for four years.

Before they were taken into captivity, nurses and doctors in Hong Kong worked in hospitals with ever dwindling resources, under the supervision of the Japanese.

Nursing Sister Daphne Ingram was a prisoner of war in Hong Kong from Christmas 1941 until September 1945. By early 1942, there were growing concerns about how to feed patients with dysentery.

To try and cure eye trouble, soya bean milk was given

At a meeting between senior nursing and medical staff, the decision was taken to put “rice through the mincer and then rolling it with a bottle to try to make ground rice”.

She recalled eventually persuading their Japanese guards to provide the nurses with hens and a rooster in order to have eggs for those patients with gastric problems.

Nevertheless, as the occupation of Hong Kong progressed, the limited access to food became a serious problem and Daphne and her colleagues needed to use all their ingenuity to provide even a semblance of a balanced diet.

“I also worked in a malnutrition clinic twice a week and gave injections of vitamin B, as many people got beriberi. To try and cure eye trouble, soya bean milk was given. To provide vitamin C we were encouraged to make pine needle tea.”

Facing starvation

Nursing Sister Phillis Briggs was interned in Sumatra from 1942 to September 1945. In June 1942, she recalled the appalling state of the rations supplied: “Half a rotten smelly cabbage was thrown in the road for us to collect and some days we only had rice.”

Between December 1942 and early 1943, Briggs recounts almost obsessively the food they consumed and how it was prepared.

“Nothing was ever wasted – eggshells were crushed and powdered – if we had fish, the bones were boiled then pounded into a rather gritty powder after being dried in the sun. We sprinkled this on our rice hoping it would provide some calcium.”

By 1944 all but the wealthiest internees, who could buy food on the black market, were malnourished and suffering from starvation. As Sister Briggs along with her other nursing colleagues had lost all their possessions at sea following the bombing of the Mata Hari – the ship on which they had evacuated Singapore – the black market was largely closed to them.

In May 1944, she wrote: “Ate chopped up banana skins for the first time, which helped fill a corner – the fruit of the bananas were given to the sick.”

Rarely discussed

Providing food and nutrition during these times was essential, not only to actual life, but to their understandings of life worth living.

The feeding work of nurses in wartime is critical both for the health of the soldier and also for their belief that life can be lived. In the internment camps in Japanese occupied territories, the critical need for nurses to feed their civilian patients took on heightened significance, yet has been rarely discussed in the scholarship of this theatre of war.

“As I see it, and this I think is the nurse’s gift, the attitude of mind I find myself possessed of is this. One would not under any consideration, whether for justice, or retribution or anything else, add one iota to the human suffering of today.

“Instead with all that tradition has handed down to us from Florence Nightingale’s time, I would take each human skeleton, be whatever race they may, and use every bit of dietetic knowledge and nursing skill to relieve this scourge of human suffering whatever it is.

“So I believe would all true nurses who have been given, through their training schools the true ideal of service. One would not under any consideration add one iota to the human suffering of today."

Dorothy Behenna, a British public health nurse published this polemic in the Nursing Times, just four months after she was released from her three and a half years’ internment in the Philippines.

Although nursing and medical staff interned in the Philippines had fared better than many imprisoned under the Japanese in the Second World War, they had suffered significant hardship; particularly a lack of food.

Nevertheless, as the quote above demonstrates, Behenna’s concern lay not with her own emaciated and nutritionally depleted body, but that of others all over the world, who were starving and in need of expert nursing knowledge and skill to return them to health.

Indeed, she argued, it was a “nurse’s gift” that she thinks not of revenge, but of saving the lives of the hungry.

Image credit: Australian War Memorial

More information

- Join the RCN History of Nursing Forum.

- Read the latest RCN Magazines history features.

- The Australian War Memorial website, which provided the above image for this article, also has a significant amount of historical material on nursing available which members might want to explore.