In April 1922, nursing staff at the Radcliffe Asylum locked themselves into wards with their patients for a sit-in strike.

Events escalated from there, and the strike was described in the newspapers as having “passed through its closing stages amongst scenes of the wildest description” in what became known as the Battle of Radcliffe.

Union history

Radcliffe first opened its doors two decades earlier to provide mental asylum (as it was then called) for patients across Nottinghamshire. By the time of the dispute, it had over six hundred inpatients, and like all asylums at this time, its wards were segregated by sex.

This meant that patients were cared for by nursing staff of the same sex, so there was a much higher ratio of male nurses in mental health institutions, called asylums at the time, than in general hospitals, a distinction which continues to the present day.

Many of the nursing and domestic staff were members of the National Asylum Workers’ Union (NAWU), founded in 1910. The union had grown rapidly, so that by 1922 it had a membership of 15,195. Of these, approximately 46% were women.

In the aftermath of war

Following the cataclysmic events of the First World War, the country experienced an economic downturn. As the recession took hold, mental asylums in England needed to make cuts.

As a result, there were a series of disputes in other asylums which were mostly successful but some, such as one held at Exeter City Asylum in 1919, were not so effective.

But in February 1922, Nottinghamshire County Council, who ran the asylum through the Radcliffe Asylum’s management committee, decided to reduce staff pay, while at the same time increasing the working hours from 60 hours a week, inclusive of mealtimes, to 66. At the union’s branch meeting, it was decided that staff would accept the wage cuts but not the increased hours.

The patients were all sympathetic to us, and on the female side they fought the police

By the end of the month, all the staff were let go, and in order to be re-employed they had to sign a form agreeing “to carry out faithfully all instructions of the Committee of Visitors, and to loyally obey the Officers of the Mental Hospital hereby appointed by the committee to put their orders into operation.”

There would be serious consequences for those who didn’t sign. They would lose both their jobs and accommodation – which was a particular concern for married male staff who had families to support. At the time, female staff were required to be single.

A week later, when this deadline was passed, none of the female staff had agreed to the terms, nor did a few of the men. NAWU members instead decided to take action.

The sit-in

On 11 April, a sit-in strike began. Female nursing staff took the lead, and they were supported by kitchen and domestic workers. Some of the male staff joined in and three out of the six male wards on the ground floor were occupied.

In taking this action, the staff were still able to care for their patients and could not be accused of abandoning them. In response to these actions, the visiting committee sacked the striking staff for “gross insubordination.”

Events reached their climax the next day on the afternoon of 12 April. At 1pm, asylum management arrived at the doors of one of the male wards with 25 bailiffs, more than 60 policemen and a group of what were described as “strike-breaking artisans”.

Fighting back

The strikers turned fire hoses on them until the water was turned off at the mains. The artisans tried to unlock the doors but found that the staff had jammed them with home-made keys.

The bailiffs then took over and started to break down the doors with crow bars and fought their way across improvised barricades to take back control of the wards.

According to the Daily Sketch “after a fierce hand-to-hand struggle, the nurses on strike in Radcliffe Asylum were overpowered and ejected by the police […] Insane inmates joined in the struggle on the side of the strikers. Many people were injured, windows were smashed and the furniture of three of the wards was reduced to matchwood.”

One of the strikers, a male nursing student at the time, Herbert Hough, recalled these events vividly: “There was a battle of course, particularly on the female side. The patients were all sympathetic to us, and on the female side they fought the police.”

As each ward was taken over, the staff were taken to the nurses’ sitting room where they reportedly sang “Rule Britannia”.

They were allowed to collect their belongings and left the asylum in two motor charabancs (an early form of bus) and were taken to the Black Lion pub in the nearby town, the scene of pre-strike union meetings.

"After a fierce hand-to-hand struggle, the nurses on strike in Radcliffe Asylum were overpowered and ejected by the police […] Insane inmates joined in the struggle on the side of the strikers. Many people were injured, windows were smashed and the furniture of three of the wards was reduced to matchwood."

Fallout

Many staff were given overnight accommodation by sympathetic villagers, but they dispersed in the morning, thus ending what one local newspaper described as the “most sensational strike of modern times.”

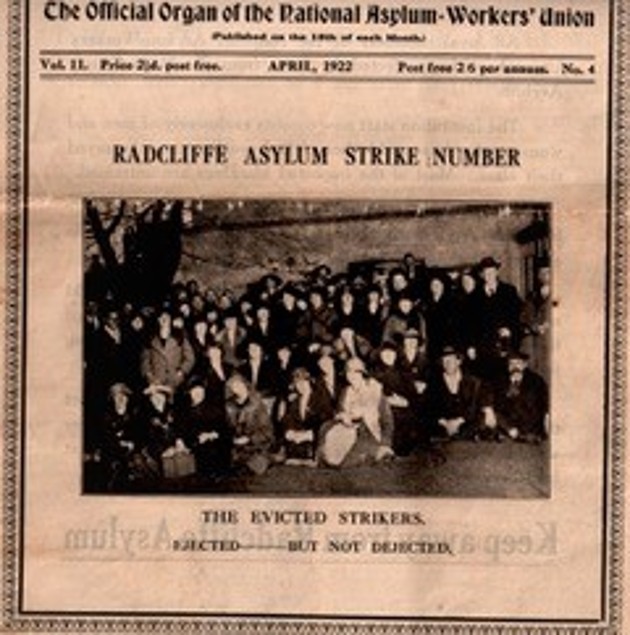

The failure of the sit-in led to the strikers losing their jobs and homes. Altogether, 73 staff had been forcibly ejected and sacked for misconduct: 18 male and 43 female nurses, four housemaids, four kitchen staff, two hall porters and two laundry maids.

Many of the dismissed staff went on to experience severe difficulty finding work, so much so that the union claimed that they had been blacklisted. Others were forced to rely on the union for strike pay and had to disperse all over the country to find employment.

Meanwhile, the hospital lost a large percentage of its staff, including all the trained nurses and all the senior female nurses, so new and mostly inexperienced staff had to be quickly recruited. According to Herbert Hough, “it was a long time before they got a really settled staff,” which in turn was unsettling for patients.

He also described the senior staff such as the matron, Ellen Leaver, and medical superintendent, Dr Samuel Lloyd Jones, as being caught in the middle of the dispute. Both were ill after the strike and left the institution within three years.

The union paid out £3,000 in strike pay to its members, subsequently lost 2,000 members and came close to bankruptcy. It was to be several years before it regained its militancy and attempted further action.

One hundred years on

Christopher Hart wrote in his book Behind the Mask: Nurses, Their Unions and Social Policy: “It was, and is, extraordinary to think of nurses barricading themselves into wards and turning firehoses on police officers and bailiffs.”

Nursing Times and Nursing Mirror – which were both dominated by general nurses at the time – condemned the strike, which further exacerbated the poor relationship which existed between these two branches of nursing.

Historians have argued that the strikers did not fit the image of the profession that general nursing leaders wanted to promote, compounding the idea that mental health nurses were not always seen as “real” nurses by their peers.

It was, and is, extraordinary to think of nurses barricading themselves into wards and turning firehoses on police officers

Additionally, because the strike was led by female staff, fighting on their barricaded wards, showing great courage, they could hardly be described as “angels” – a classic stereotype for nurses.

“The women nurses gave a lesson in militancy and collective determination to the men,” wrote historian Mick Carpenter, which challenged expectations of female behaviour at the time.

Although it is now 100 years since these events took place, industrial unrest remains relevant among nursing staff. It is important to remember the Radcliffe strikers, who fought to prevent further erosion of their working conditions.

As Frank Lynch, the general secretary of the union that succeeded the NAWU, remarked, the end of the Radcliffe strike was a dark day, “which almost bankrupted the union, but it[s] overall lesson – that patient’s welfare and safety must be a nurse’s first priority – is as true today as it was all those years ago.”

More information

- Join the RCN History of Nursing Forum.

- Read the latest RCN Magazines history features.

- Read more from the Nottinghamshire Nursing History Group and including research from Dr Rosemary Collins. The group also has a significant amount of historical material on nursing available which members might want to explore.