Meet the members who care for people seeking treatment to bring their body into alignment with their gender identity

The discreet brown door to the Gender Identity Clinic in Hammersmith, London, reveals nothing of the life-changing conversations going on inside. It’s where people are referred when they’ve made the decision to physically transition, usually starting hormone therapy and often pursuing genital reconstructive surgery.

“I can’t tell you what it feels like when you first come here,” says Holly, who started her transition four years ago.

“You spend so long keeping everything inside, plagued by confusion and self-doubt, then you arrive and for the first time you feel accepted. The barriers come down and the floodgates open. The staff here really do understand.”

You spend so long keeping everything inside, then you arrive and for the first time you feel accepted. The staff here really do understand

One of those staff members is Lucy Evans, a specialist nurse with the endocrine team. It’s her role to monitor the physical effects on people having hormone therapy, liaise with their GPs who prescribe and administer treatment in the community, and keep tabs on the general health and wellbeing of those in her care.

“It’s an incredibly busy service,” she says. “There are around 7,000 people actively under the care of the clinic but many more are on the waiting list. It currently takes more than a year to get an appointment at any UK clinic, then another year between follow-up appointments here in London.”

Lucy

Lucy

It can take some time for people to be endorsed for hormone therapy by the gender specialist psychiatrists and psychologists - there are risks and irreversible effects and so thorough discussion and assessment must occur.

People need to provide evidence that they have transitioned socially, so presenting in their gender identity full-time at home, work or university before they’re approved to proceed to surgery.

We assess the impact of hormone therapy on different aspects of life. We take a very holistic approach

“Once people are on hormone treatment I’m responsible, along with the endocrinology doctors, for supporting and monitoring health and wellbeing,” explains Lucy.

“We check blood results, blood pressure, weight and height, and assess the impact of hormone therapy on different aspects of life such as energy levels, mood, motivation, libido and sexual health. We take a very holistic approach.”

No small step

Starting treatment is not a decision taken lightly. Hormone therapy needs to be administered for life by those who choose to transition.

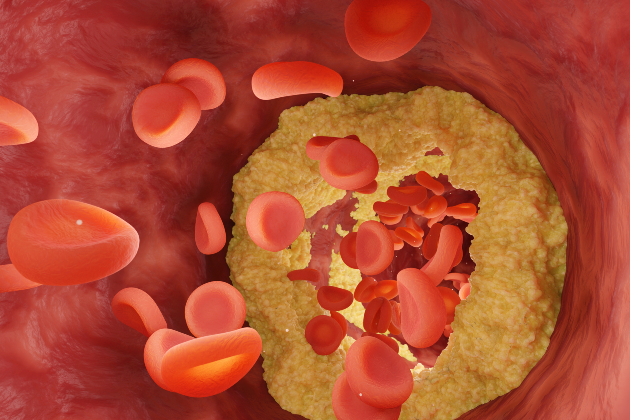

Though generally safe, it does carry some risk, such as the increased risk of blood clots, for example deep vein thrombosis with oestrogen treatment, and an increased risk of stroke on testosterone treatment. There is also the impact on reproductive options to consider.

“That’s why staying healthy is so vital for people on hormone therapy,” says Lucy. “It’s particularly important that people don’t smoke and are not overweight as both hormones and smoking exacerbate the risk of clotting and stroke.”

Those coming to the clinic do so from a number of routes. Most through a referral from their GP, from all over the country, others once they have turned 18 having previously been seen at the specialised children and adolescent gender identity development service in London.

It’s particularly important that people don’t smoke and are not overweight as both hormones and smoking exacerbate the risk of clotting and stroke

For Holly, it was later in life that she realised she may have gender dysphoria.

“I knew something wasn’t right for many years,” she says. “I struggled with relationships and didn’t feel comfortable in the body I was in. But it was going to a fancy dress party that was the turning point for me. Being dressed as a woman felt right and I fell into a deep depression afterwards.

“It sparked a period of intense soul searching and for a while I was deathly afraid of myself. But I consider myself to be lucky. I had the courage to see my GP and that was when I was referred here.”

The mental health of people who experience gender dysphoria is of serious cause for concern. A trans mental health study conducted by British researchers in 2012 showed that 84% of participants had contemplated suicide, 35% had attempted it, and 25% had done so more than once.

It sparked a period of intense soul searching and for a while I was deathly afraid of myself. But I consider myself to be lucky

When people are referred to the gender identity clinic, their psychological health is of primary importance.

“Not because being trans means you’re mentally ill,” Holly hastens to add. “But because when you realise you were born in the wrong body, your whole world turns upside down. Your outlook on life changes completely. It’s not easy to forget 40 years of being a boy.”

And yet confusion, curiosity and fear often means people who are transgender get a rough deal from health services.

A Transgender Equality Report published in 2016 found that trans people encounter significant problems in using general NHS services due to the attitude of staff who lack knowledge and understanding. The NHS is failing to ensure zero tolerance of transphobic behaviour, it concluded.

It’s an issue specialist nurse Iffy Middleton can corroborate. Having worked with trans people for 15 years and assisted in more than 500 gender reconstructive surgeries, she has witnessed the poor care that can be provided when health professionals show ignorance towards treating people who have transitioned.

“I got a panicked phone call from a doctor in A&E recently,” she says. “One of my ladies had gone there with complications with her catheter after surgery.

“The doctor said he couldn’t find the urethra. It turned out he hadn’t done a thorough physical examination because he felt embarrassed. Now I’m sorry. But that’s not acceptable. Can you imagine how scared that person must have been? Situations like that make my blood boil.”

Although Holly says she’s received “amazing, sensitive and professional care” from NHS staff, she too feels there could be improvements in how trans people are communicated with.

“Health care professionals may not have much, if any, experience of dealing with us face to face so they may feel unsure how to make that first contact,” she reflects.

“First off, relax, we’re looking for your help and expertise just as any other person is. Secondly, ask how the person would like to be addressed, as in title and name. Physical signs may lead you adrift.

“If you have any doubts just make your first greetings gender neutral. Being misgendered is something most trans people are very sensitive about. Remember to smile and enjoy your first trans patient. On the whole, we’re a very interesting bunch.”

Ask how the person would like to be addressed. If you have any doubts, make your first greetings gender neutral. Being misgendered is something most trans people are sensitive about

Iffy, or Saint Iffy as she’s affectionately known by her patients, is a vocal advocate for the transgender community. Not happy to accept the constant underfunding that she feels contributes to poor care, she walked out of her NHS staff job in protest some years ago.

She has been working bank shifts in endocrine care and was the lead nurse for gender reassignment surgery at the private Parkside Hospital before recently moving to Australia to help imrpove services for trans people having procedures in Melbourne.

“I love my job,” she says as she embarks on her new challenge. “It’s so rewarding to see a person get what they want, and to have played a part in helping them feel happy. It’s an honour really, to support them in making such a significant life change.

“You develop relationships with such a wide range of people, some of whom you’ll always remember. So I’ll never stop fighting for my patients, it’s just a shame that there is still so much fighting to do.”

It’s so rewarding to see a person get what they want, and to have played a part in helping them feel happy

With Iffy moving overseas, Lucy is among just a handful of nurses left working in the specialty in the UK, though she’s keen to encourage more. “It’s such a varied, exciting and innovative role,” she enthuses.

“I only registered three years ago and yet I’m learning so much and am in a position to really influence care beyond my position here.”

Lucy has developed information for practice nurses and has been delivering presentations to support them in administering and monitoring hormone therapy to people where they live.

Her next aim is to encourage student nurses to undertake placements at the clinic and to campaign to have gender dysphoria and care for trans people on the curriculum for nursing students.

When you transition, there are times that you’re at a cliff edge. You jump off and think, oh crikey, I’ve done this. Then you open your eyes and the world keeps turning

For Holly, the work of specialist nurses is vital. “When you transition, there are times that you’re at a cliff edge. You jump off and think, oh crikey, I’ve done this. Then you open your eyes and the world keeps turning.

“Those are such monumental moments. You need support and understanding to get through that.”

The view from here

Rachael Ridley, staff nurse

First and foremost, I’m a nurse. That’s how I see myself but when I was a child, I knew I was in the wrong body. Later on in my life I decided I had to do something about it. I couldn’t live a lie.

I’ve worked on the same ward since 2000 and in January 2005, I started to live full-time as a female. I had to do this for two years before I was able to have surgery. I was terrified. I was worried I’d lose my job. At the time, there was no policy in place for supporting trans people and my trust wasn’t sure what to do.

I went to speak to a manager on an adjacent ward who was also an RCN steward. I said “I’ve got something important to tell you” and once I’d finished, she said “Is that all?” That put me at ease and she reassured me that I wouldn’t lose my job.

I’m sure it was difficult for my co-workers because they were used to a male colleague and now suddenly they had Rachael. Some of them had difficulty getting their head around it but on the whole, I got a lot of support. I’d say 99.9% of people at work were supportive. Now I don’t even think about it. Nobody does. I’m just Rachael, a staff nurse.

Three patients have refused to be cared for by me. I chose to avoid caring for them but my deputy director of nursing, who has always been supportive, asked me “what would have happened if you were the only staff nurse on duty?” It’s a good point.

Now, my trust is finalising its trans policy for staff and patients which I’ve helped to develop. I explained that although people were supportive, I would have liked someone at work to turn to for advice and emotional support and this is something they’ve taken on board.

Has my experience as a trans person made me a better nurse? Yes, because it’s made me a better person. I’m more aware of marginalised groups of people in society and how they might feel. I think about that a lot, especially in my caring role.

Want to improve care for trans people?

The RCN has published guidance to help nursing staff provide fair care for trans and non-binary people. It provides information about gender dysphoria, an overview of hormone therapy and surgical procedures and gives advice on supporting trans and non-binary people to live healthy lives.

What is gender dysphoria?

Gender dysphoria is a condition where a person experiences discomfort or distress because there’s a mismatch between their biological sex and gender identity.

Biological sex is assigned at birth, depending on the appearance of the genitals. Gender identity is the gender that a person identifies with or feels themselves to be.

While biological sex and gender identity are the same for most people, this isn’t the case for everyone. For example, some people may have the anatomy of a man, but identify themselves as a woman, while others may not feel they’re definitively either male or female.

This mismatch between sex and gender identity can lead to distressing and uncomfortable feelings that are called gender dysphoria. Gender dysphoria is a recognised medical condition, for which treatment is sometimes appropriate. It’s not a mental illness.

Information courtesy of the NHS. For more information, visit the NHS website.